Mary Seton Watts is known for being the wife of the Victorian painter and sculptor George Frederic Watts and relatively little known for her accomplishments as a ceramicist, creator of a prosperous potters’ guild and an extraordinary mortuary chapel. Venturing to the Watts Gallery Artists’ Village in a picturesque region of Surrey brings her legacy to light.

Mary Seton Watts is known for being the wife of the Victorian painter and sculptor George Frederic Watts and relatively little known for her accomplishments as a ceramicist, creator of a prosperous potters’ guild and an extraordinary mortuary chapel. Venturing to the Watts Gallery Artists’ Village in a picturesque region of Surrey brings her legacy to light.

My days slip by without a scrap of artistic work being done. Why women fail in art is answered to myself ‘because of the little things in life’.

Ah, if we could but work fanatically in the light of our own 19th century thought … fight against immorality, seeing the injustice of recent social opinions, against the sacrifice of sacrificing women, against intemperance, against the desire for wealth, & the hideous inequality of distribution to living in at least the universal brotherhood! A return to our true balance, man with woman, both with nature, which means health, beauty, innocence.

Excerpts from The Diary of Mary Watts 1887 – 1904, Desna Greenhow (ed.), London, 2016

Until recently historians have overlooked Mary Seton Watts’s inspiring story of determination and talent. There is an entry about her husband, the painter and sculptor George Frederic Watts (1817 – 1904), ‘England’s Michelangelo’, in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and in Oxford Art Online; Mary (1849 – 1938) is left out in the cold. Fortunately her accomplishments are attracting wide acclaim as the house, gallery and mortuary chapel she inspired have been restored, and her influence is warmly acknowledged and detailed in the exhibition space and during the tour of the house. The most notable publication for general interest about Mary was issued last year: The Diary of Mary Watts, edited by Desna Greenhow. Indeed, an entry about Mary for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is being written while I write.

Undoubtedly Mary was profoundly happy being married to George who was thirty-two years her senior (she was 36 and he was 69 when they wedded), and devoted to him throughout the seventeen years of their companionable union. Their marriage afforded Mary an enriching and enterprising artistic life, although George was the focal point of the couple’s time together. The frustrating ‘little things in life’ were but minutiae compared with the ‘big things’ Mary achieved once she married. The marriage sparked liberation rather than constraint. Even if Mary had lived in a world where women’s rights were not a battleground, she might not have blossomed so.

The couple’s bond was strengthened by their promotion of socially progressive reform. George and Mary Watts were advocates of the women’s suffrage movement, the campaign against restrictive clothing, and the trade union movement. They envisaged a civic and civilising role for art and design, one that could positively transform the lives of the disadvantaged. We see Mary’s passionate social perspective, a driving force for her altruistic projects, revealed in the second quotation above.

Indeed, the artistic work of both Mary and George reflected their humanitarian values. Mary used symbolic humanistic imagery from different cultures and religions for her ceramic designs. She was especially inspired by Celtic imagery and imagery from illuminated manuscripts, such as the Book of Kells and Lindisfarne Gospels. George Watts created allegorical images, with historical, religious and mythological references, which reflected disturbing contemporary issues, such as homelessness, famine, social inequality and the depersonalising effects of industrialisation. Contemporaries viewed him as a philosophical painter, a visionary, and considered his portraiture equally soulful; it was not stylised. Many of his subjects, such as Thomas Carlyle, Walter Crane, Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris, John Stuart Mill, Canon Samuel Barnett (who with his wife, Henrietta, helped to improve the lives of the poor in Whitechapel, and establish the Whitechapel Art Gallery) and Josephine Butler (a prominent suffragist), were socially progressive.

“I paint ideas, not things…my intention is not so much to paint pictures which shall please the eye, as to suggest great thoughts which shall … arouse all that is best and noblest in humanity,” revealed George Watts.

Mary (nee Fraser-Tytler) was born in 1849 into a literary family, identified with the Scottish intelligentsia, which assuredly nurtured her social views. She grew up on her family’s estate in the Scottish Highlands, at Aldourie Castle, Loch Ness (a baronial edifice now available for holiday letting!). Her father was a civil servant. She attended the National Art Training School in South Kensington (which was later called the Royal College of Art) where the curriculum emphasised design and decorative arts rather than fine art. There she enrolled in a clay modelling class, taught by the established sculptor Aimé-Jules Dalou, whose large public masterpieces can be seen in Paris. The course had a significant influence on her later work as a decorative designer; Mary eventually made her ‘mark’ in clay. Later, Mary attended the Slade School of Art. (At the time, women were only allowed access to draped male nudes in drawing classes!)

After her formal training, Mary rented a studio in London where she could practise portraiture. She also began teaching clay modelling classes at a boys’ club in Whitechapel. This experience encouraged Mary’s developing interest in the teaching of craft skills to the ‘working classes’ and her involvement with the Home Arts and Industries Association (HAIA). The Association aimed to teach classes in rural crafts, such as wood carving, basket weaving and book binding, to ‘working class’ people in rural communities, so that these handicrafts would not die out, and they could provide enjoyable and employable occupation – a sharp contrast to dehumanising factory life.

For many years Mary Fraser-Tytler and George Watts enjoyed a ‘student teacher’ relationship before they courted and later married in 1886. They had met in 1870 when Mary visited Little Holland House, George Watts’ home in Kensington. (George had been married briefly to the actress Ellen Terry.) The introduction was strengthened through the couple’s shared connections to the Isle of Wight, where George kept a house, and Mary had friends and family relations; their circles overlapped. Mary recalled that ‘Signor’ (as referred to by his friends) had a most courteous manner, evocative of chivalric days.

Once wed, the couple honeymooned in Egypt, Turkey and Greece. The rich range of cultures she encountered and their differing symbolic languages captivated Mary. Her interest proved to be a foundation for her artistic endeavours on the estate the Watts would eventually establish in a quintessentially English village in the rolling hills of Surrey. The idea of living in the fresh air, in a rural community, greatly appealed to the Wattses for the sake of George’s health. Friends living in the village of Compton encouraged them to build a house near them, which the Wattses did, starting in 1890. The house (with studios), which was named Limnerslease, from “limner” meaning artist and “lessen” meaning to glean, was designed by Sir Ernest George. He was highly regarded for his country houses that reflected the local vernacular. His practice was referred to as “the Eton of offices”. Lutyens was one of his pupils.

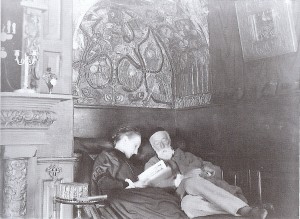

When we tour the house with Desna Greenhow, we see the truly unique series of white low relief gesso panels Mary created for the ceiling in the entrance Hall and the ceiling in the adjoining Anson Red Room on the ground floor. In the Hall are five panels representing different spiritual cultures: Buddhism, Hinduism and Judaism and those of ancient Assyria and Egypt. The symbols in the Anson Red Room are meant to suggest the joy of work. Imagery includes an Egyptian winged sun, bees, butterflies, birds, corn sheaves and grapes, symbolising energy, industry and the fruits of labour. Unfortunately, Mary Watts’s panelling for the alcove or ‘niche’, where she would read to the slightly deaf George in the evenings, has disappeared; the alcove is now unadorned. (It was meant to help amplify Mary’s voice.) The couple especially enjoyed the work of Rudyard Kipling and Jane Austen; Tolstoy’s War and Peace, and Gaskell’s Cranford also appealed. They read about religious philosophy and scientific discovery. The Pall Mall Magazine was a favourite.

When we tour the house with Desna Greenhow, we see the truly unique series of white low relief gesso panels Mary created for the ceiling in the entrance Hall and the ceiling in the adjoining Anson Red Room on the ground floor. In the Hall are five panels representing different spiritual cultures: Buddhism, Hinduism and Judaism and those of ancient Assyria and Egypt. The symbols in the Anson Red Room are meant to suggest the joy of work. Imagery includes an Egyptian winged sun, bees, butterflies, birds, corn sheaves and grapes, symbolising energy, industry and the fruits of labour. Unfortunately, Mary Watts’s panelling for the alcove or ‘niche’, where she would read to the slightly deaf George in the evenings, has disappeared; the alcove is now unadorned. (It was meant to help amplify Mary’s voice.) The couple especially enjoyed the work of Rudyard Kipling and Jane Austen; Tolstoy’s War and Peace, and Gaskell’s Cranford also appealed. They read about religious philosophy and scientific discovery. The Pall Mall Magazine was a favourite.

In 1895 the local Parish Council purchased land for a new cemetery on the edge of Compton village. The graveyard surrounding the village church of St Nicholas was becoming quite full. The Wattses decided to finance the building of a mortuary chapel for the cemetery, determining that its creation would involve the community. In her biography of her husband, Mary wrote, “so that by this means a special and personal interest in the new graveyard would be acquired by the workers”.

The Grade I listed Watts Chapel is Mary’s masterpiece. The fact that Mary Watts was not a trained architect did not mean that she could not dictate its architectural form, a small single cell space, a circle, intersected with the cross of faith, purposely reminiscent of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. A local architect advised her about structural details and the use of local materials. The chapel looks as if it is a neo-Byzantine cathedral built for Lilliputians.

Mary’s designs for the imaginatively patterned external terracotta carvings are drawn from Christian iconography and imagery predating Christianity. One attribute, for example, is the circular ‘path’ around the chapel, a frieze featuring imagery symbolising human attributes such as truth (an owl and scales), hope (see the peacock), light (an eagle, for instance) and love (see the pelican). The symbol of the Tree of Life is repeated on the buttresses and bordered with columns patterned with ‘running water’ signifying the river of life. A local carpenter carved the entrance doors; a local blacksmith made the hinges.

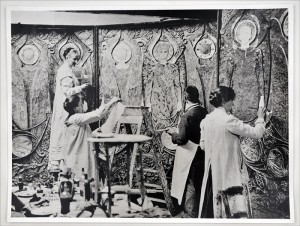

Villagers, many of whom were unemployed agricultural workers, helped to make the terracotta tiles covering the walls of the chapel. Mary trained them at evening classes, which she held in her studio. When the structure and exterior decoration were finished in 1898, the chapel was consecrated.

During the next six years, Mary worked on the relief work and painting for the interior of the chapel. This work is detailed and Mary did much of it herself. There is a display at Limnerslease showing how the mouldings for the interior were created. The base consisted of chicken wire, sacking hemp and rough plaster, which was covered with gesso, a mixture of fine plaster and animal glue, and raked with a comb to create texture. Hatting felt, sewing tape, and more layers of gesso helped to build up the design. Finally, the panels were painted and gilded with gold leaf. There is painting on smooth gesso as well.

During the next six years, Mary worked on the relief work and painting for the interior of the chapel. This work is detailed and Mary did much of it herself. There is a display at Limnerslease showing how the mouldings for the interior were created. The base consisted of chicken wire, sacking hemp and rough plaster, which was covered with gesso, a mixture of fine plaster and animal glue, and raked with a comb to create texture. Hatting felt, sewing tape, and more layers of gesso helped to build up the design. Finally, the panels were painted and gilded with gold leaf. There is painting on smooth gesso as well.

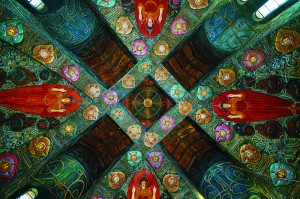

The decorative scheme is presented in four panels. We see seraphs and angels, and a golden girdle – a band – circling around the chapel decorated with emblems of the Trinity, Celtic motifs. The Tree of Life is rooted below and grows through the band, spreading its branches up towards the heavens above. Over the altar is a painting by George Watts entitled The All Pervading. The interior is very colourful, dazzling.

After the exterior of the chapel was completed, Mary determined to harness  the modelling skills of the villagers, so that they should not be forgotten. This endeavour would have an enterprising and civic value. She started a pottery, which would produce sundials, gravestones, wall plaques, garden pots, balustrades and ornaments. Cottages were built for the workers. The Compton Potter’s Art Guild, as the pottery eventually was named, closed in 1956. Liberty of London became one of its regular customers. The store sold a brooch based on one of Mary’s chapel motifs. Gertrude Jekyll used some of the Compton pots in her garden designs. The Royal Botanical and Royal Horticultural Societies awarded medals to the pottery for its products, which were also exhibited at international industrial fairs, such as the St Louis World’s Fair, 1904.

the modelling skills of the villagers, so that they should not be forgotten. This endeavour would have an enterprising and civic value. She started a pottery, which would produce sundials, gravestones, wall plaques, garden pots, balustrades and ornaments. Cottages were built for the workers. The Compton Potter’s Art Guild, as the pottery eventually was named, closed in 1956. Liberty of London became one of its regular customers. The store sold a brooch based on one of Mary’s chapel motifs. Gertrude Jekyll used some of the Compton pots in her garden designs. The Royal Botanical and Royal Horticultural Societies awarded medals to the pottery for its products, which were also exhibited at international industrial fairs, such as the St Louis World’s Fair, 1904.

In 1902, George and Mary bought a three-acre site nearby on which they built a gallery, in the Arts and Crafts tradition, to display Watts’ pictures and sculpture for public viewing. Part of the building was also used as a hostel for the pottery apprentices.

Mary’s productive life continued to flourish after her husband died in 1904. She continued managing and designing for the pottery alongside running the Watts Gallery. She wrote The Annals of an Artist’s Life about George Watts and a detailed account of the chapel decoration, The Word in the Pattern: A Key to the Symbols on the Walls of the Chapel at Compton.

After Mary’s death in 1938, most of the contents of the house were sold. During the Second World War, the house was used by Ardente, a company manufacturing naval radar and sonar equipment. Later, after the Second World War, the house was divided into three and each part was sold. In 2011, all three parts of the house came onto the market, and the Watts Gallery Trust was able to acquire each part and gradually begin a programme of restoration. From a long sleep the Artists’ village has gradually awakened. An extensive outreach programme ensures that what Mary created still has firm and productive community links, as Mary would have wished. When you visit, you will see that George Watts was also married to a great visionary artist.

Notes:

For further information about Watts Gallery Artists’ Village, please refer to www.wattsgallery.org.uk. You can visit the Gallery, house (guided tours only), studios, chapel, cemetery and visitors’ centre, which features temporary exhibitions. (It was converted from its former use as part of the pottery.) The teashop serves delicious teas and light lunches.

Read The Diary of Mary Watts 1887 – 1904, edited by Desna Greenhow, Lund Humphries, London 2016. Mary called her diary ‘Fatima’. She writes clearly and in a relaxed and warm-hearted manner. We learn about major figures in the late nineteenth century who were socially progressive, and associated with the Arts and Crafts movement, and the nature of their friendships with the Wattes. We enjoy commentary about the Wattes’ intimate moments with each other, and how they progressed with their work. Dr Greenhow has extracted the most revealing passages including helpful and well-written annotations and introductions to chapters.

Also on permanent view is the De Morgan Collection, a collection of ceramics and oil paintings by Evelyn Pickering De Morgan and her husband William Frend De Morgan. They were one of the most influential artistic couples of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Evelyn was also, in common with Mary Watts, a pioneering female artist and one of the first women to attend the Slade School of Art. Her parents insisted that she had to be chaperoned! Her work was widely exhibited and compared to that of George Watts; it also revealed personalized, allegorical interpretations of mythological, religious and moral themes, sometimes from the woman’s perspective. The colours and patterns of Islamic pottery inspired William; he re discovered the art of lustre decoration. He was a good source of advice for Mary about running her pottery. For a while he contributed to William Morris’s decorative enterprise. William was also a novelist! (See also http://artisticmiscellany.com/2016/01/22/evelyn-and-william-de-morgan/)

Of course, one learns much about George Watts while visiting this most inspiring setting; appreciating Mary entails knowing about one of the major sources of her artistic enlightenment and development, her husband. Unlike Mary he was not born into a privileged family. His father was a pianoforte maker and tuner. His family life has been described as “strict sabbatarian and evangelical”. His talent for drawing emerged when he was very young and was encouraged by his father. When he was ten he joined the studio of the draughtsman and sculptor William Behnes, a family friend. Eventually he began to earn money with portraiture, a source of funds that continued throughout this life. His interest in spiritually meaningful art inspired him to try large-scale history painting, and, in time, work imbued with social realism, such as The Irish Famine. He did receive commissions for creating spiritual paintings and murals. Watts was the first British artist to have a solo exhibition of his work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Ruskin described him as one of the five “geniuses…I have known”.

Former President Barack Obama’s favourite painting is believed to be Hope by George Watts. It supposedly encouraged Obama on his path towards the White House. He learned about the painting when he was listening to a sermon by the Reverend Jeremiah White, his controversial former pastor. The painting was the focus of the sermon. It depicts a hunched and blindfolded ragged young woman who sits atop a globe, plucking a single string on her wooden lyre. She still has the “audacity to hope” believed the priest. The words formed part of a rousing electoral speech by Obama and inspired the title of his book, The Audacity of Hope.

The images above are of the exterior of the Watts Chapel, Mary and George reading together in the niche, Mary Watts and Compton villagers preparing the interior of the Watts Chapel, and the interior of the Watts Chapel. All images courtesy of Watts Gallery – Artists Village, all images C Watts Gallery – Artists’ Village.