During lockdown I received a present from my good friend, Suzanne Bardgett. It was a copy of her recently published book, Wartime London in Paintings. Featured are 82 paintings by 36 artists of scenes in the capital during the Second World War, some upsetting, some colourful and cheering, some wondrous for the sense of the industrious they exude, some tender; all are definitely novel, as they are settings one would only have encountered in the war; and all are definitely enlightening, offering us slices of social and military history. All, too, are scenes from the daily life; familiar urbanscapes and ordinary folk coping as best they can with the dramatic changes affecting their lives. They are not epic war pictures, but rather images of gallantry in the course of the everyday. Bardgett’s captions are illuminating and articulate.

We see roof spotters looking for enemy aircraft; a panic stricken zebra escaping from the zebra house at London Zoo after it was bombed; a shelter with people huddled together while sleeping in Camden Town under a brewery on Christmas Eve; a bombed cellar next to Holborn Viaduct being lined to form an emergency water tank; a house collapsing on two firemen in Shoe Lane; convalescent nurses making camouflage nets; members of the Auxiliary Fire Services (AFS) standing on the shores of the Serpentine Lake in Hyde Park handling giant hoses through which water was pumped from the lake; members of the Home Guard outside a pub in Maida Vale eyeing an attractive woman as she walks by.

The pictures were commissioned or purchased by the War Artists Advisory Committee (WAAC), a government agency established within the Ministry of Information in 1939, headed by Sir Kenneth Clark. Its raison d’être was to compile a comprehensive artistic record of Britain throughout the war. Some 6000 depictions were amassed.

They were given to the Imperial War Museum, other London museums and regional galleries. During the war some of the pictures were featured in public exhibitions, at the National Gallery and at regional galleries. (The key archival source for the book is the WAAC’s correspondence held by the Imperial War Museum.) As Head of Research at the Imperial War Museum, Bardgett is in an ideal position to appreciate their significance as part of the history of London.

Some of the artists whose work was included in the record are well known today, such as Edward Ardizzone, Paul Nash, Graham Sutherland, Henry Moore and Stanley Spencer. Many of the artists themselves endured the privations of war and many were serving in the war while they painted or sketched. Some lost their studios and their work.

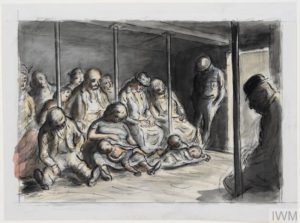

Edward Arrdizzone’s watercolour (see below) In the shelter captures “the sheer exhaustion of spending nights in shelters where there was nowhere to lie down”. He spent nights sketching in the London Underground where the train tunnels were used as shelters.

them with children sleeping on their knees. Some sleep on the floor. In the foreground there is an old man wearing a bowler hat, also

asleep. The warden stands with his hands in his pocket, leaning against the wall near the door, his head bowed. Copyright: © IWM.

There are many other such sketches to his credit. Ardizzone was one of the small number of WAAC salaried war artists. He is well known for his children’s books and in particular the stories of Little Tim.

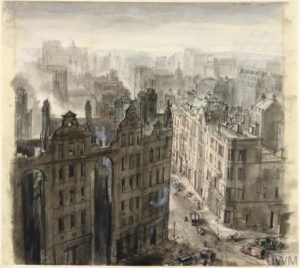

What was depicted in A House Collapsing on Two Firemen, Shoe Lane, EC4 was actually witnessed by the artist Leonard Rosomon. (See image at top.) One of the firemen was killed and this haunted Rosomon for the rest of his life. The second fireman was the writer William Sansom who reflected the experience in a short story The Wall, which was published in Horizon magazine. Shoe Lane is still a narrow street, now lined with glass fronted office blocks. There is a plaque dedicated to Sidney Holder, the fireman who lost his life.

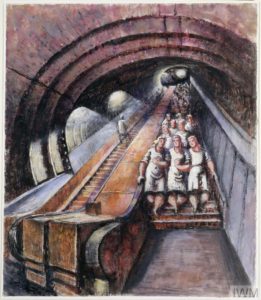

Frank Dobson’s An Escalator in an Underground Factory shows factory workers descending to a secret underground factory for their shift. The communters worked for Plessey, the electrical company which supplied radio sets to the RAF. The five mile long factory, producing shell and bomb cases, aircraft parts and radio components, was accessed from three stations. The factory was in a new extension of the Central Line which ran close to the company’s Ilford factory .

I was especially drawn to the book because the paintings reveal a dystopian period, evocative of our own times, one where the very nature of life has changed substantially and unimaginably. Alas, during the Second World War, people could see what they feared coming. What we fear now is invisible; where the scourge in our lives in 2020 lurks is a mystery.

I was also pleased to receive the book because the pictures are so captivating; yes, I confess that I would wish to see many of them on my walls. The collection offers a wealth of artistic styles to enthral; it is not a tribute to an art movement. It is a tribute to humane artistic responses to a time of great strife.

The richly illustrated book is also commendable because it brings to light many of the fine pictures of wartime we have in the Imperial War Museum and elsewhere in Britain. Suzanne Bardgett’s achievement is a unique contribution to our artistic heritage, as well as our nation’s history.

***

Wartime London in Paintings is available from the Imperial War Museum. https://shop.iwm.org.uk/p/27588/Wartime-London-in-Paintings