The museum tells a fascinating story about the history of the postal service. Film, photographs, posters, stamps, post boxes, a bicycle, a stagecoach, a postal van and explanatory panels make up a rich array of exhibits. What makes the visit a ‘one and only’ is that visitors can also ride on the Mail Rail, the driverless underground railway that used to transport mail across London between the mainline railway stations and sorting offices of London. The railway began operating in 1927 and stopped eighteen years ago. Its existence meant that the transporting vans did not have to travel through heavy London traffic.

As the museum suggests, one could say that the postal system is the first social network. For from its beginning, until not long ago, people did not regularly communicate by text, email, mobile, iPad, laptop and desktop computer. Facebook, Instagram and tweeting were the imaginations of science fiction. Communication by post, telegrams, telexes and land lines used to be the primary means of contact throughout the world. Are they now intimations of archaism?

King Henry VIII established Britain’s first postal system. Under his authority a network of post boys, some as young as 11, on horseback or foot, took post from one city to another. No longer would individual couriers be the main carriers. However, this system could only be used by the king. Charles I opened up the service to the public. Prices were determined by the number of pages and paid by the recipient. (Some letters could cost as much as twelve loaves of bread!) Hence, sometimes letters were ‘cross -written’ such that the writing was at two or more angles. This could make the letter look like a block of squares and must have been quite confusing to follow.

Mail destined for addresses overseas travelled by ship. The crews and post faced many hazards such as piracy, icebergs and storms. There was a time when on land the post was carried throughout the kingdom by stagecoaches, referred to as mail coaches, with armed guards riding on the outside of the coach.

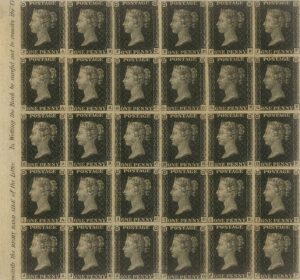

In 1840, a dramatic change in the postal service took place. Postage would be paid by the sender and the charge would be based on weight, making it far less expensive to send a letter. The stamp could not be used again as it was ‘cancelled’ with the date and place of posting. With lower rates, people were more  inclined to write to friends and relatives all over the world. The world’s first postage stamp was called the Penny Black (pictured left) as letters weighing up to 15g or half an ounce would cost a standard one penny.

inclined to write to friends and relatives all over the world. The world’s first postage stamp was called the Penny Black (pictured left) as letters weighing up to 15g or half an ounce would cost a standard one penny.

Post boxes were introduced to save people time travelling to the post office. If one lived quite far away from a post office, mailing a letter could be quite a cumbersome task. Early post boxes were blue, green as well as red. In 1857, the system of having postal districts was started. This made it easier to sort out and deliver the post. Letters would no longer be distributed by one central office but by local offices.

Postal workers began to use motorcycles to deliver the post in the early twentieth century. During both World Wars pigeons were used to carry mail. The British used about 100, 000 pigeons to carry post during the First Word War.

During the Second World War, about 250,000 pigeons were ‘employed’. A British award for animal valour, the Dickin Medal, was given to 32 pigeons of various nations.

The process of designing new stamps begins up to five years in advance of when they will be sold. Royal Mail researchers decide which subjects the stamps will focus upon. They think about events that will occur in five years’ time and themes that are and will be important to the nation. People are welcome to send in ideas, too.

Four designers are then chosen to create designs illustrating the chosen topics. The designers may have some experience of designing stamps or none at all. Different artistic forms may be used to create an image, such as photography, painting, graphics, cartoons, sculpture and collage. The artists must abide by two rules: the monarch’s head must be part of the design and the stamp’s value must be shown.

The completed designs then go before the Stamp Advisory Committee and ‘proofs’ and ‘essays’ are produced showing how the stamps will look with a particular design in the actual size they will be. An essay is the proposed design for a stamp submitted by the artist. It may not necessarily be the final design, but one which is developed. A proof is a trial printing of a stamp from a die or printing plate before actual stamp production.

Finally, Royal approval is required. The King, if he follows his mother’s tradition, will review every stamp design before it is issued and ready for you to purchase at the post office! The Royal Mail issues about fifteen sets of stamps on different themes each year. Each year one of the sets of stamps reflects the theme of Christmas.

Until about seventy years ago, British stamps were roughly similar, with a few exceptions, to the Penny Black, which featured prominently a head of the monarch. But in 1965 the then Postmaster General Tony Benn introduced a tradition whereby commemorative stamps would be issued annually to mark events or subjects of national importance, not only passing events as had traditionally been the case. The ‘new’ tradition started when Tony Benn addressed a letter to the public at large asking for ideas about how stamp designs could be improved.

The artist David Gentleman replied with a long letter suggesting that we could celebrate many interesting aspects of the nation’s life, such as birds, transport, architecture and regional landscapes, not only past events. Perhaps we can credit Mr Gentleman as the person who prompted the change in perspective.

Now there are  about fifteen new issues every year, each one focussing on a particular subject. They are available for sale only for a limited period. Stamps available for an extended period of time are called ‘definitives’; they show only the head of the monarch. Pictured left is the definitive showing King George VI.

about fifteen new issues every year, each one focussing on a particular subject. They are available for sale only for a limited period. Stamps available for an extended period of time are called ‘definitives’; they show only the head of the monarch. Pictured left is the definitive showing King George VI.

This year a set of six stamps was launched to pay tribute to David Gentleman who has designed more than 100 stamps for Royal Mail between 1962 and 2000. Royal Mail and David Gentleman have collaborated in choosing some of his most famous and influential images. These are ones from sets marking the 25th anniversary of the Battle of Britain (1965, a quartet of planes), the 900th anniversary of the Battle of Hastings (1966, a Bayeux tapestry illustrating a Norman ship), Social Reformers (1976, Thomas Hepburn, the pioneer of the first miners’ union, represented by the hewing of coal), British Trees (1973, an oak tree), British Ships (1969, an Elizabethan galleon) and National Productivity Year (1962, upward facing arrows, symbolising increasing propsperity, placed over an image of the United Kingdom next to the logo of National Productivity Year).

There are other artists who have contributed designs to the Royal Mail. In commemoration of the Royal Academy’s 250th anniversary, the work of six Royal Academicians was featured on a set of six stamps: Tracy Emin, Grayson Perry, Yinka Shonibare, Barbara Rae, Norman Ackroyd, and Fiona Rae. Perry’s stamp, titled Summer Exhibition, shows himself in the form of statues and paintings exhibited at the Royal Academy. Other notable stamp design artists are Arnold Machin, Eric Gill, and David Hockney. Machin designed the royal portrait that featured on the United Kingdom’s coins from 1968 to 1984.

The youngest designers will be the eight whose creations were chosen for a set of ‘Covid heroes’ stamps. In 2021, Royal Mail launched a competition through schools, parents, home educators, carers and clubs asking young people aged 4 to 14 to create designs reflecting the work of key workers and volunteers during the pandemic. There were over 600,000 entries. One winning entry featured Sir Tom Moore; another featured an NHS cleaner; another pictured her family’s delivery driver. Despite his own personal losses, he never stopped helping others.

What makes stamp design unique is that not only is its publication so tiny, and the specifications so detailed, but also because behind each design lies a vast wealth of history, an insight into the past and the present. A courier service could never inspire such industry and enlightenment.

For further information about The Postal Museum, please visit https://www.postalmuseum.org/ There is a cafe at the museum and a shop.