The painter Evelyn Pickering De Morgan (1855–1919) and her husband, William Frend De Morgan (1839–1917), a ceramic designer and bestselling novelist, were both Spiritualists. They believed that the body is left behind after death while the soul – the personality of the person who has died – travels to a different dimension, a spiritual world; and these souls or spirits can communicate with the living. When I visited the De Morgan Centre in Wandsworth, London, where the work of this loving and enterprising couple is displayed, I wondered if there’s a shard of truth in this system of belief.

A feeling of warmth pervades the atmosphere. The spacious galleries and glass display cases are sensitively lit. The informative panels are free from jargon. There are no cordons barring me from examining the innovative creations and how the deep autumnal colours the artists used complement each other’s work – brushstrokes of synergy? It’s not surprising that an acquaintance of the De Morgans noted that they were ‘one in sympathy, in intelligence and its direction, one in tastes and in perfect companionship…He believed in her Art and she in his’. One is inspired to discover the seeds that bore the fruit of the artists’ talents and their shared intellectual interests. Are the spirits of William and Evelyn enthusing me?

Evelyn’s family was rich and well connected. Her father was a barrister, a QC; her mother was descended from an aristocratic family. Evelyn was brought up so that she would make a ‘good marriage’ and bring up well-behaved children. Artistic endeavour was encouraged only in so far as it would be a suitable accomplishment for a lady. Evelyn’s mother regarded Evelyn’s artistic dedication as a ‘painting mania’. But from an early age Evelyn was determined to be an artist. She secretly painted in her bedroom, stuffing rags under the door to prevent the smells of paint and turpentine from escaping.

Eventually Evelyn’s parents allowed her to attend the Slade School of Art but only on condition that she was chaperoned. The Slade was one of the few art schools at the time that accepted women and allowed them to study live nude (albeit half-draped) models. She won prizes and was also honoured with a Slade scholarship. She later studied in Florence and Rome. Her uncle, Roddam Spencer Stanhope, an artist and member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, encouraged her and helped to support her financially. Evelyn pursued her career in London and it was not long before her work was exhibited in galleries such as the Dudley, the Grosvenor, the Fine Arts Society, and the Walker Art Gallery.

Although Evelyn’s paintings have been compared to the work of Botticelli, George Watts, her uncle and Edward Burne-Jones, her achievement was distinguished for its painterly style – the use of rich, saturated colours, bold but not bright, subtle tones and carefully crafted composition and detail. Her subject matter was also distinguishing: personalized, allegorical interpretations of mythological, religious and moral themes, such as the ethics of war. Evelyn would reinterpret myths by reconfiguring the story around a woman’s perspective. Many of her paintings were imbued with spiritualistic themes and references to the claustrophobic world of Victorian and Edwardian women.

Although Evelyn’s paintings have been compared to the work of Botticelli, George Watts, her uncle and Edward Burne-Jones, her achievement was distinguished for its painterly style – the use of rich, saturated colours, bold but not bright, subtle tones and carefully crafted composition and detail. Her subject matter was also distinguishing: personalized, allegorical interpretations of mythological, religious and moral themes, such as the ethics of war. Evelyn would reinterpret myths by reconfiguring the story around a woman’s perspective. Many of her paintings were imbued with spiritualistic themes and references to the claustrophobic world of Victorian and Edwardian women.

William De Morgan was the second of seven children born to Augustus and Sophia De Morgan. His father was a mathematician who became a professor at University College, London. William’s mother was involved in prison reform, the anti-slavery movement and the Suffragette movement. She helped to found London’s Bedford College for Women, later part of London University. Sophia was also a Spiritualist and published a book on the subject. This interest inspired that of William and Evelyn, who also anonymously published a Spiritualistic book, which focused on automatic writing.

William began studying Classics at University College when he was 16, but an interest in art inspired him to enrol in evening classes and thereafter to study at the Royal Academy Schools. Soon William realized, through his developing friendships with major figures in the Arts and Crafts Movement such as Henry Holliday (a stained-glass artist and fellow student), Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, that he was more attracted to the decorative than the fine arts.

In 1861, Morris established the firm Morris, Marshall, Falkner & Co to produce goods that could be complementary, forming part of a decorative scheme: stained glass, textiles, wallpapers, and tiles. Interestingly, tiles had just begun to take on a decorative rather than solely functional role in architecture and interior design, being installed, for example, in fireplaces, church floors and walls. Traditionally, tiles were used for roofing and in dairies and public lavatories as they were easy to clean. De Morgan contributed to Morris’ enterprise by decoratively painting tiles, especially, and stained glass, using the firm’s stylishly simple ‘English’ floral designs as prototypes.

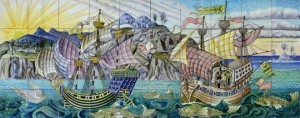

Later De Morgan distinguished himself when he began producing designs in the Turkish ‘Iznik’ style with rosette, leaf and stem-like shapes, flowers such as carnations, tulips, and hyacinths, and ogee patterns, painted against a white background with the characteristic cobalt blue and turquoise colours. De Morgan also produced red lustred ware featuring animals such as dragons, hares, lizards, fish, antelopes, snakes, and birds such as owls and peacocks, all of which could appear both ‘grotesque’ and humorous.

Morgan’s interest in the artistry of lustre happened accidentally when he was captivated by the iridescence reflecting from the stains of silver nitrate on stained glass that resulted from over firing. He wondered how one could purposely produce this effect. Although De Morgan could have learned about the technique from other sources – reduced-pigment lustre had been produced since the 9th century AD in Iraq, Italy and Spain and other regions – he worked out his methods on his own and became an authority. De Morgan was not much interested in the making of the pots themselves. It was the decorative work and the chemical and scientific challenges of firing and glazing that attracted him.

Several achievements distinguish De Morgan as a celebrated ceramicist. Such are the way he used reduced-pigment lustring to adorn his wares – notably the tonality and polychrome effects he created with varied concentrations of pigment and several firing stages – his designs, and his method of transferring the designs onto tiles while preserving their hand-painted quality.

Moreover, success in the process is never guaranteed, which makes his work that much more special. Reduced-pigment lustring involves an already-glazed and fired ceramic painted with a metallic oxide, such as gold, silver or copper, carried in a clay medium – De Morgan used gum Arabic as a thickener – which is re-fired in a reducing atmosphere (one that removes oxygen from the glaze) in order to leave a metallic film on the glazed surface. Achieving the desired tonality would involve several firings. How the heat and pigment would interact could never be predicted with certainty.

De Morgan’s technique is different – and less reliable – than that producing resinate lustres, liquidized metallic preparations (using resin-balsam) used as glazes for the first firing, leaving the object looking as if it’s solid or plated gold or silver. It is also different from reduced-glaze lustres, which incorporate metal compounds in the glaze and ‘coat’ the entire ceramic surface.

De Morgan set up his own workshops and a showroom in Chelsea (where later, after their marriage, the couple also lived), hiring ceramic decorators and a kiln master. For a time he had workshops in Merton Abbey, south London, and Fulham. De Morgan’s Islamic styling caught the eye of Frederic (later Lord) Leighton, who commissioned him to complete the panels of original Islamic tiles that he had collected and was installing at the new Arab Hall at Leighton House. Other commissions included producing tiles for the Tsar of Russia’s yacht, the Lavadia, and for P & O Liners, picturing ships at sea and cities.

Evelyn not only believed in William’s talent but also invested in his business on several occasions when the firm was financially in trouble. William was not a good businessman. He admitted that his business was ‘very ill Demorganised in fact!’ In 1905, after he was struck with neuritis, De Morgan abandoned creating ceramics and devoted his creative energy to writing. (See notes below.)

Evelyn’s younger sister, Mrs Wilhelmina Stirling (1865–1965), who collected Evelyn’s paintings and William’s ceramics in her beautiful home, Old Battersea House, had always wanted a memorial to the couple’s work and life to be established. In 1968, the De Morgan Foundation was formed, and the nearby borough reference library, when vacated, proved to be an ideal exhibition and educational site. The Centre opened in 2002.

What makes the De Morgans unusual among many couples who have shared a love of art and pursued its creation is that they respected and supported each other’s endeavour, never seemingly in competition, and also that they shared intellectual interests – in Spiritualism and the Suffragette movement, for instance (William was Vice President for the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage in 1913). Indeed, have any other such couples inspired a museum devoted to their work? Their spirits have much to teach us.

Notes:

The novels of William De Morgan are: Joseph Vance (1906), Alice-for-Short (1907), Somehow Good (1908), It Can Never Happen Again (1909), An Affair of Dishonour (1909), A Likely Story, (1911), When Ghost Meets Ghost (1914), The Old Madhouse (1917), The Old Man’s Youth (1921). All of them were first published by Heinemann. The last two were issued posthumously, having been completed by Evelyn.

For further information about the De Morgan Foundation and the collection of work by Evelyn and William De Morgan, please refer to http://www.demorgan.org.uk. Unfortunately the gallery – the Centre – in Wandsworth featuring the work of the De Morgans closed in 2014. The Foundation provides access to the collection through loans, exhibitions and tours.

Photographs of Galleon tiles painted by William De Morgan and The Gilded Cage by Evelyn De Morgan, © De Morgan Foundation.

This article first appeared in Cassone: The International Online Magazine of Art and Art Books in the September 2012 issue.