We had planned to spend a week walking in the mountains in the Italian commune known as Grizzana Morandi, once home of the painter and printmaker Georgia Morandi (1890–1964), from whom it gets its second name. Many of his landscapes are of the surrounding countryside. We were hungry for tranquillity rather than artistic exploration.

We had planned to spend a week walking in the mountains in the Italian commune known as Grizzana Morandi, once home of the painter and printmaker Georgia Morandi (1890–1964), from whom it gets its second name. Many of his landscapes are of the surrounding countryside. We were hungry for tranquillity rather than artistic exploration.

After a late change of plan, however, we followed Morandi in spirit to his birthplace, Bologna, and thereafter explored the outlying region of Emilia Romagna, where, peculiarly, relatively few foreign tourists visit. Indeed, there are few guidebooks about Emilia Romagna and more detailed information is generally in Italian.

The region is a passageway through the verdant plains and hills of the Po Valley, leading from the west to the east of Italy. It is not surprising that we sensed an air of bourgeois prosperity wherever we ventured, for Emilia Romagna is one of the most prosperous regions in Europe. Many of its cities and major towns are near the Via Aemilia, a Roman road (and a usually congestion-free thoroughfare), linking Rimini on the Adriatic coast with the town of Piacenza, once a prime garrison, further north.

In the central part of Bologna, the region’s capital, one can walk along nearly 40 kilometres of colonnaded pavements, admiring the salmon, warm yellow and ochre-coloured stuccoed buildings. The core of the city is the Piazza Maggiore, overlooked by Europe’s supposedly fifth-largest church, the Basilica di San Petronio, which was never finished, hence its incomplete brick front façade. The church was intended to be larger than St Peter’s in Rome, but 169 years after construction had commenced in 1390, Pope Pius IV blocked further building by diverting funds to another project.

Heading northwards from the Square we found San Colombano, a beautifully restored, deconsecrated mediaeval church featuring original frescoes and an accessible crypt. The church houses a splendid collection of nearly 90 European, ‘antique’ and folk musical instruments assembled over a period of 50 years by the octogenarian organist, Luigi Tagliavini. Many of the instruments, which date from the 16th to the 20th centuries, are used for concerts. Viewing the collection and supporting information helped us trace the development of instrument making and how music and music making are perceived in various cultural contexts. The early keyboard instruments are elaborately adorned with stylized and colourful pictorial images and decorations. Notable artists include the Mannerist Belisario Corenzio, Giacomo A. Mannini and Giuseppe Zola. Within an oratory, two chapels, galleries and the body of the church, are organs; square, upright and grand pianos; harpsichords, clavichords, spinets, dulcimers; wind instruments such as oboes and clarinets; automated instruments; and folk instruments such as a mandolin, bells, an accordion and ocarinas. The ocarina family of wind instruments dates from ancient times. Ocarinas are small, enclosed clay or wooden spaces – some look like eggs – with several holes on the surface and a projecting mouthpiece. We partake in a musical feast, with so few other guests.

Nearby is a beautiful art and history library housed in the former church of San Giorgio in Poggiale. The architect of the transformation, Michele de Lucchi, is internationally honoured (he was awarded an honorary doctorate from Britain’s Kingston University). De Lucchi has designed lamps and furniture for Italian and European businesses and museum buildings in Berlin, Rome and Milan; for ten years he was Director of Design at Olivetti. The books, dating from the 1500s, belong to the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio in Bologna, and one may read them on site. The shelves lining the walls look as if they are reaching for the heavens. The low bookcases stretch across the floor of what was once the nave. The shelves, tables and chairs are made from a light wood, possibly beech. The library is wondrously bright, and spacious – the sense of lightness overwhelms. Abstract paintings cover the walls of the side aisles. There are two striking sculptures, one seemingly a cylindrically shaped entrance porch of wooden blocks, the other being a rounded, nearly five feet high, stack of books with a bell atop – a liberty bell?

We viewed a wealth of Morandi’s work at MAMbo – Museo d’Arte di Moderna di Bologna. The permanent collections are not vast; the work of contemporary artists is a strong feature. The classical façade masks a strikingly minimalist interior.

One highlight of our visit was a piano concert of works by Bach played by a young French pianist, Remi Geniat, in the porticoed courtyard of the 16th century Palazzo dell’Archiginnasio. The building was once the historical seat of the University of Bologna, the oldest university in Europe (established in 1088).

In Ferrara – the centre of which also features a pavement network of colonnades – we walked along the nine kilometres (six miles) of Ferrara’s red brick curtain of defensive walls, which were built during the Renaissance with ducal sponsorship. They are much more extensive than Lucca’s better-known protective walls. We strolled along the embankment or below by the moat, on gravelled or unmade tracks, passing through grasslands of wildflowers, parkland, and by bastions, embrasures, iron gates, private dwellings and social housing estates. The trail is a well-used thoroughfare as we saw many Ferranese carrying shopping, gently cycling, jogging, pushing prams, and power walking while talking on their mobiles.

In Ferrara – the centre of which also features a pavement network of colonnades – we walked along the nine kilometres (six miles) of Ferrara’s red brick curtain of defensive walls, which were built during the Renaissance with ducal sponsorship. They are much more extensive than Lucca’s better-known protective walls. We strolled along the embankment or below by the moat, on gravelled or unmade tracks, passing through grasslands of wildflowers, parkland, and by bastions, embrasures, iron gates, private dwellings and social housing estates. The trail is a well-used thoroughfare as we saw many Ferranese carrying shopping, gently cycling, jogging, pushing prams, and power walking while talking on their mobiles.

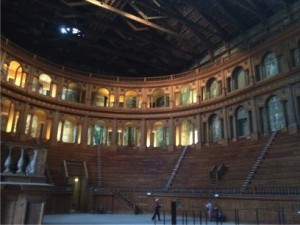

In Parma, the wooden Teatro Farnese, sited within the vast Palazzo della Pilotta, astonished us. Originally the wood was painted to resemble marble and bronze. This is supposedly the first surviving theatre with a permanent proscenium arch. The construction allowed for movable scenery and a stage deep enough to enable ten rows of sliding flats, which hide the wings of the theatre and can be used for scenery. In front of the stage there is a large U-shaped area originally intended for dancing and royal processions. For the inauguration of the theatre in 1628 it was flooded with water for a naval battle with storms, shipwrecks and sea monsters. Tiered rows of benches ring this area, which is six feet above the floor and enclosed behind a balustrade. Above the benches are two rows of arches topped by a small gallery with statues. The Farnese was heavily bombed during the Second World War and reconstructed using the original design, though the wood was left unadorned. The walls reveal original frescoes painted by Lionello Spada.

The Farnese was designed in 1618 by Giovanni Battista Aleotti for Ranucci I, the Duke of Parma and Piacenza, to honour the passage of Cosimo II de’ Medici through Parma on his way to Milan to visit the tomb of San Carlo Borromeo. Alas, the trip was cancelled and the opening of the theatre was celebrated ten years later to mark the marriage of Margherita de’Medici and Odoardo Farnese, Rannucio’s son. The theatre can accommodate about 3000 spectators.

Within the Palace is also the National Gallery of Parma, featuring an extensive collection of pictures by artists such as the city-born Correggio and Parmigianino, Schedoni, Canaletto, Van Dyck and Hans Holbein the Younger. There is a head study of the Madonna by Leonard da Vinci. The glorious, quiet, palatial setting of the work enhances the experience of viewing – there are no quivering echoes of audio guides.

Oscar Wilde came to mind when we visited Ravenna, for while at Oxford he received the Newdigate prize in 1878 for his poem about the city: ‘O lone Ravenna, many a tale is told/Of thy great glories in the days of old;/Two thousand years have passed since thou didst see/Caesar ride forth to royal victory…’ For Ravenna is renowned for its early Christian mosaics and monuments. Among the eight city buildings designated as World Heritage sights, is the red brick octagonal church of San Vitale, a two storey, red brick octagonal edifice, dating from 547 AD. Its circling ambulatory with marble columns encloses a central space beneath a great cupola. The colourfully rich and glittering mosaic art – astoundingly dense – depicts Biblical stories, landscapes, a wealth of angels, flowers, fruit, birds and animals, and the Roman Emperor Justinian, Empress Theodora and court officials.

There’s much more to share, but space limits. I’m puzzled as to why we were able to enjoy so much without being elbowed by people looking at the ‘must sees before you die’. Have the genteel people of Emilia Romagna chosen not be self-publicists? Does the flat landscape deter visitors? Time after time, I will return.

Notes:

To see modern Italian art in London, visit the Estorick Collection, which is housed in a Georgian villa overlooking an elegant Georgian square in North London. The building was once a factory producing artificial flowers and thereafter the studio and offices of Colin St John Wilson, who designed the British Library’s new building. Eric Estorick (1913–93), an American sociologist and writer (biographer of the politician and former British ambassador to Moscow, Stafford Cripps) and Salome, his wife, amassed the collection. Estorick was influenced by his friend, the American photographer Alfred Steiglitz, and his visits to the Gallery of Living Art in Washington Square College which featured the work of Picasso, Leger, Miro, Matisse, Georgio de Chirico and Piet Mondrian. Later, an art teacher, Arthur Bryks, sparked Estorick’s interest in modern Italian art and in particular the Futurist movement. The Estoricks favoured representational work with a strong figurative content. The Collection includes work by Umberto Boccioni, Amedeo Modigliani, Georgio Morandi, Zoran Music, and Gino Severini. For more information, visit www.estorickcollection.com.

Photographs of the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna, and the Teatro Farnese, ©Stephen Kingsley.

This article first appeared in Cassone: The International Online Magazine of Art and Art Books in the August 2014 issue.