Women are under-represented in the art world – because they are women. Until very recently a woman’s art was much less likely than a man’s to be displayed in a gallery or museum, included in a renowned permanent collection, the subject of a ‘retrospective’ or voluminous critical analysis, or sold for a high price at an auction house. A woman was also less likely to be appointed as head of an illustrious renowned art establishment or prestigious higher educational art history or fine art department. Established collections feature far more portrayals of nude women than they do of art by women.

Although these statements merit provisos and elaboration, generally speaking, the art world has been gender biased rather than gender balanced. Attempting to posit statistics to the contrary would be a fruitless exercise. The times they are a changing, fast, but it may be a long while before gender imbalance in the art world becomes history.

In this light one hails the collection of modern and contemporary art at Murray Edwards College, Cambridge, acknowledged as one of the most significant of its kind in Europe. Indeed, it is one of the most unusual public art collections you are likely to view in the near future, if only on account of the nature of its setting. When my husband and I visited we were the only people purposely looking at the work, although many were nonchalantly passing it by as they went about their lives, aware and appreciative of its existence.

The College houses about 400 works of art–paintings, prints, drawings, photographs, ceramics and sculptures created by women, some famous, some emerging lights. About 90 per cent are on display (some in private but accessible areas). They are arranged along the walls of wide, bright corridors, in between the pigeonholes of the students and notice boards; on the walls of the heavenly, fibreglass domed dining hall; in the circular stairwell and the cavernous lower ground floor.

At Murray Edwards, one has the time to reflect upon each work; you can look slowly around Elisabeth Frink’s Easter Head 1 (1989), contemplating the man’s facial expression. His slightly raised eyebrows and large wide eyes gaze upwards, as if to suggest that he is experiencing some sort of revelation or rebirth. You are not pressed to move along a line of others, following in impatient abeyance to auto-guides.

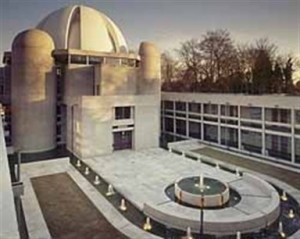

Moreover, the modernist architecture of Murray Edwards – the original Grade II* listed building and its subsequent extensions – complements the presentation, allowing us to see the work easily and comfortably. It allows light and space to infuse the building; there is minimal architectural detail; and the geometric corridors and passageways flow uninterrupted by doors and defined openings, all encouraging concentration, rather than distraction and detraction. And as with modern and contemporary women’s art, the building embraces new forms, modes of expression and ways of thinking about the way we live.

The raison d’etre of the College makes it a near perfect setting for the Collection. Until recently known as New Hall, Murray Edwards was founded in 1954 for women students when the University had the lowest proportion of women undergraduates of all the universities in the United Kingdom. Girton and Newham were the two other Cambridge colleges at the time accepting women. (Now Lucy Cavendish and Newnham are the only ‘women only’.) As the College aims to do, the Collection celebrates women’s achievements.

The evolution of the Collection started in 1986 when the College acquired American born Mary Kelly’s Extase just after her period as Artist in Residence at Kettle’s Yard and at the College. Interestingly, the work, six laminated photopositive screen-prints and acrylic on Perspex, is of particular relevance to women. The work is part of a larger series, Corpus, which is divided into five sections – Menace, Appel, Supplication, Erotisme and Extase – these terms were used by J.M. Charcot, a French, 19th-century neuro-pathologist, whose studies of female hysteria influenced Freud. Kelly is parodying, through her choice of media and configurations, stereotypical and supposedly authoritative ‘male’ images of women, challenging a male dominated status quo.

The gift and its thematic context prompted the President at the time, Dr Valerie Pearl, to envisage the potential of a permanent collection on display of 20th century art by women. This would enhance and work in tandem with the College’s purpose as an educational institute: to encourage students to prosper intellectually, creatively and spiritually.

Dr Pearl, together with her adviser, Ann Jones, an experienced curator and arts development coordinator, drew up a list of about 100 women artists practising in Britain (but not necessarily British born), and wrote to each of them explaining their goal and asking if they would be willing to donate work to the Collection. Unexpectedly, the response was overwhelming – a 75 per cent success rate. Artists such as Judith Cowan and Maggi Hambling gave outright or lent work indefinitely. Artists’ families and friends donated work. Judy Chicago, Anne Redpath and Barbara Hepworth are a few more of the artists whose work has been donated since. Alas, there’s no acquisitions budget: donations are vital.

During my visit I was especially drawn to Jila Peacock’s oil painting The Rose Chalice (1966). Her image is of a man and a woman, both gently curved, ‘Matisse-like’, in relaxed reclining positions, whose hands are just about to join over a rose coloured chalice. A fish, a symbol of Christ, swims in a pool at the bottom of the picture. The picture evokes a sense of the ethereal and the sacred quality of enduring love. It inspires hope by confirming the immortality of love.

Portrait painter Emily Patrick’s oil, The Artist with her Daughter (1990), is equally atmospheric, with its subtle tones and shapes, and mere hints of friends and family figures in the background, implying a supportive rather than oppressive purpose. The mother and baby share the same reflective expression, with clear skin and eyes and wide foreheads. The frame, of rope, is symbolic of bonding or more graphically the umbilical cord. An unusual sculpture is Tessa Pullan’s Dobbin (1980), composed of strips of light wood, exuding a sense of a sinewy pony in gentle motion.

Next time I visit there may be more surprises. The Murray Edwards Art Committees, internal and external, continually work to develop the Collection, relying on the interest and expertise of art historians, current and former museum directors, students and the Bursar and College Convenor, among others. A three-year grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund enabled the appointment of a curator from 2008 until 2011; and the College is raising funds to secure a new curator. There’s an endowment fund for art work conservation. Temporary exhibition space offers women artists the chance, without charge and commission, to showcase their work for up to one month.

The Collection presents an illuminating narrative about the achievements of women artists in the 20th and 21st centuries – filling a regrettable and unjustified gap in museum art collections. In some contexts it reveals gender-based issues and how women artists have chosen to express them in captivating and creative ways, exploring stereotyped and historic perspectives of womanhood. It’s not avowedly women’s art; it is good art, great art; and determinedly eclectic in theme and genre, though one former President has noted that the Collection began in a ‘more feminist spirit’.

Praise be to Dr Pearl for inspiring this fine tribute both to art and to women who engage in serious artistic enterprise, enabling students to have role models who are not nuclear scientists or prime ministers. Being equal – ‘on the same level’ – doesn’t necessarily mean working in a traditional male professional bastion. At Murray Edwards, art is valued both as a profession and as a civilizing and energizing force in society. Hence, the purpose of the Collection may never become obsolete.

Notes:

How many established women sculptors can you name? This list of 22 is by no means inclusive. Camille Claudel (1864–1943), Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (1875–1942), Malvina Hoffman (1887–1966), Louise Nevelson (1899–1988), Barbara Hepworth (1903–75), Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010), Anne Truitt (1921–2004), Yayoi Kusame (b.1929), Magdalena Abakanowicz (b.1930 ), Elisabeth Frink (1930–93), Nicki de Saint Phalle (1930–2002), Eva Hesse (1936–1970), Phyllida Barlow (b.1944), Rebecca Horn (b.1944), Ann Christopher (b.1947), Alison Wilding (b.1948), Cornelia Parker (b.1956), Sokari Douglas Camp (b. 1958), Rachel Whiteread (b. 1963), Sophie Ryder (b.1963), Alice Anderson (b.1972).

For further information about the collection, guided tours, viewing artwork not on display or in the private areas of the College, visit www.art.newhall.cam.ac.uk.

Other places to visit in Cambridge:

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge: a half-hour walk towards the city, from Murray Edwards College. Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge: a 10-minute walk, towards the city, from the College. www.kettlesyard.co.uk. See also the artisticmiscellany article on Kettle’s Yard .

The photograph is of Murray Edwards College. ©Murray Edwards College.

This article first appeared in Cassone: The International Online Magazine of Art and Art Books in the June 2011 issue.