My favourite discovery – spiritual and non-spiritual – of the last five years is Persephone Books. Nicola Beauman, the founder, named the enterprise after the Greek goddess Persephone because the deity reflects the essence of her creative endeavour, to publish ‘feminist’ but not overtly ‘Feminist’ literary work. Beauman believes that the name Persephone

My favourite discovery – spiritual and non-spiritual – of the last five years is Persephone Books. Nicola Beauman, the founder, named the enterprise after the Greek goddess Persephone because the deity reflects the essence of her creative endeavour, to publish ‘feminist’ but not overtly ‘Feminist’ literary work. Beauman believes that the name Persephone

has a timeless quality; sounds beautiful; is very obviously feminine; and symbolises new beginnings (and fertility) as well as female creativity…and that is why our logo, based on a painting on a Greek amphora, shows a woman who is not only reading (the scroll) but also symbolises domesticity (the goose)…The domesticity of the logo makes it plain, we hope, that ours is a feminist press without being too overtly ‘Feminist’. Most of our books are written by women, but they are realistic not idealistic, everyday not outrageous, sympathetic not alienating and domestic not angry.

Revolving around domesticity, the product of fertility and the goddess Persephone’s sphere, the company’s fiction and non-fiction reflect the ordinary and not always so ordinary occurrences of ordinary people. The stories resonate with the inner lives of people the world over. For they explore, in differing circumstances and cultural contexts, the many shades and textures of the feelings of the human condition, such as joy, grief, love, hate, tenderness, compassion, self-doubt and loathing, dread and fear.

I have just finished reading Persephone Book No 47, The New House, by Lettice Cooper, first published in 1936. The author grew up in Leeds. She studied classics at Oxford and then worked in the family engineering business. All of her twenty novels “convey both her deep Socialist convictions and her loyalty to her Yorkshire roots”, as the publisher writes. She worked for a brief period at the literary and political weekly with Feminist sympathies Time and Tide. Later she helped to establish the Public Lending Right. The writer Jilly Cooper, the author of the preface, is married to Leo Cooper, her nephew.

The book portrays a day in the life of a family moving, for reasons of economy and convenience, from the ‘big house’, Stone Hall, located on the outskirts of a town in Yorkshire, to a much, much smaller house, overlooking a housing estate. The novel explores the memories, tensions and adjustments this inspires. It is emotionally rather than action packed.

Will the heroine, Rhoda, the unmarried, extremely accommodating, good natured daughter cut loose from Natalie, her egocentric, vulturous, widowed mother? “It’s such a good thing, Natalie thought, that Rhoda has never got married, or gone to work in London like Delia, I should have been so lonely,” Natalie thinks to herself. Will Rhoda accept a job offer in London, organised by Delia, her sister, and Delia’s fiance? Will she be a ‘care-taker’ or a woman on the brink of a new life? The blatant shallowness of Evelyn, Rhoda’s sister in law, brother Maurice’s wife, made me cringe. Would Maurice be able to resist his growing disillusionment with Evelyn’s abhorrent snobbishness?

Is there any one of us who has not faced the dilemma of wanting to shake free from stifling obligations, and yet felt compelled to oblige them? Can we fulfil dreams and a duty? Are we sometimes repelled by people’s pretentiousness to the point where we feel our insides will rupture with rage? When I feel what some of the characters express, I feel as if I am wearing their shoes.

Persephone Books was certainly not established on a grand scale. Before opening up as a ‘shop’, it was first a mail order business operating above a pub in Clerkenwell, funded by a small inheritance from Nicola Beauman’s father. Both her parents, Frederick and Eleonore, were highly respected lawyers. They emigrated from Germany to Britain in 1933, to escape from the ascendancy of Nazism. They would have been persecuted eventually because they were Jewish. They had to begin life all over again, despite their academic and professional achievements in Germany. Nicola Beauman is a journalist and biographer of Cynthia Asquith and E.M. Forster.

Persephone Books was certainly not established on a grand scale. Before opening up as a ‘shop’, it was first a mail order business operating above a pub in Clerkenwell, funded by a small inheritance from Nicola Beauman’s father. Both her parents, Frederick and Eleonore, were highly respected lawyers. They emigrated from Germany to Britain in 1933, to escape from the ascendancy of Nazism. They would have been persecuted eventually because they were Jewish. They had to begin life all over again, despite their academic and professional achievements in Germany. Nicola Beauman is a journalist and biographer of Cynthia Asquith and E.M. Forster.

Persephone Books does not commission books. Instead, it publishes out of print, “lost”, books by, mostly, women, written, mostly, in the twentieth century, in particular between the two World Wars; the settings for the books are usually in Britain, and to a lesser extent in America and Europe; one was rooted in South Africa during apartheid; another is a memoir of Stalin’s terror by Eugenia Ginzburg. Most of the books reflect a middle-class milieu; there are exceptions, such as Round about a Pound a Week by Maud Pember Reeves, a study of working-class life in Lambeth during the early 20th century.

Some of the authors published by Persephone you will have heard of, such as Enid Bagnold, Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf; others are likely to be unknown to you, such as Barbara Noble and Dorothy Whipple. Whipple is the most popular and adored Persephone author; the company has published ten of her novels. People come into the shop every day and talk about Dorothy Whipple.

The publications may be novels and short stories, diaries, memoirs, poetry and children’s, gardening and cookery books. One singular endeavour is an enlightening book of literary criticism and social history by Nicola Beauman about women writers between the wars A Very Great Profession: The Woman’s Novel 1914 – 39. First published in 1983, it set the stage for the birth of the firm; quite a few of the books explored by Nicola Beauman have since been published by Persephone. All Persephone Books feature a preface or an afterword by a writer with a particular affinity with the subject of the book.

Persephone’s 135 (at the moment) publications are still sold by mail order as well as in the company’s shop in the heart of Bloomsbury. Beautifully wrapped, the books make splendid presents. When you visit you will encounter the ‘manager’ Lydia Fellgette. Sometimes I think of Lydia as Persephone personified, as well as the steel foundation of the firm.

Persephone organises events in its ‘home’ and elsewhere, related to the stories, subjects and authors of its books. These may be talks and film showings, with lunch, tea, wine or Madeira, walking tours and visits to houses where an author lived. A book club meets once a month.

In Persephone’s “biannually” magazine forthcoming publications are introduced, explaining how they came to be, their themes and overtones. We learn about the authors’ backgrounds. There are extracts from reviews and bloggers’ sites commenting on Persephone publications. There is always an enticing extract from a book or a short story. The website is that much more expansive, supplementing and complementing the magazine. Especially compelling are Nicola Beauman’s perspectives and ‘notices’. She is not afraid, for fear of losing readers approval, of expressing her humanitarian values through her comments about current affairs and choice of exhibitions and events. No waffle or hype taints the content.

The magazine and site burst with warm colour. There are prints of paintings, watercolours, engravings – nearly always with people, and mostly of interiors, be they houses or workplaces, or shops – by not so well known and well-known artists such as Roger Fry, Evelyn Dunbar and Rex Whistler.

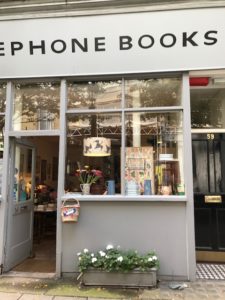

Persephone Books, the shop, captures the aura of femininity, housed on the ground and basement floors of an early Georgian building on a cobblestone street, Lamb’s Conduit, alongside a cheese shop, ‘brunch’ cafes, Italian restaurants, bespoke tailors and a funeral parlour. The light grey front has large glazed windows, allowing views of an enchanting, timeless interior. There are potted plants outside and fresh flowers on the window ledges just inside, together with Persephone merchandise. By the entrance is a basket with a pile of the biannually. The books are placed on low-level light grey shelves. Also for sale are rolled posters and framed vintage posters (“Join the Wrens”), scarves and fabrics in baskets, shopping bags, cards and postcards, notebooks and ceramics, all reflecting the cultural realm of Persephone. Rather magnanimously, a round wooden table displays books Persephone “wished that we had published”.

The books please the eye. They have light grey jackets and clotted cream coloured labels with the titles in black print. They have a timeless resonance. Historically, books did not have pictorial covers, Lydia Fellgette explains. There are different endpapers for each book. The endpapers are associated with the year or period in which the book was originally published and its story or subject. Usually they are prints of fabrics such as furnishing and dress materials, hence the textiles on sale. A matching bookmark comes within.

So, for example, for Good Evening , Mrs Craven: the Wartime Stories of Mollie Panter-Downes (short stories published in The New Yorker from 1938 – 44) the fabric chosen, called “coupons”, is one designed soon after the introduction of clothes rationing in June 1941. It shows items of brightly coloured women’s clothing against writing explaining what can be bought for how many coupons.

There are no rigid rules by which Persephone chooses what joins the list. Yes, they are mostly from the mid twentieth century. “Women wrote so well then…they were well educated, yet society was not yet ready to allow them to work outside; writing was a good compromise,” Nicola Beauman says. Differing genres attract: fiction of all sorts, which could be comedies, satires, romances, thrillers short stories ad science fiction. Non-fiction, especially memoirs, appeal. Nicola Beauman likes work with a strong theme, such as being a house husband, blackmail, childbirth, homosexuality, adultery and anti-Semitism. Beauman says that they “have to really love every book”. She is the ultimate judge, although all those involved with Persephone on a daily basis help to find and choose, explains Lydia.The books have to be page turners. Indeed, I have read numerous reviews of Persephone Books which say how devastated the reviewers felt when they reached the last pages. Lydia notes that people find that if you read one, you will read another, hence this is why some readers have a standing order for one book a month or ring up for suggestions for the “next one”. They do not publish a book because it could be a best seller; this is not important to us, she reveals, although what has made the company sustainable is the unexpected world-wide success of Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day by Winifred Watson.

Readers may suggest books. A ‘find’ could be a customer’s mother’s favourite book, such was Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day, which was adapted for film. The novel is about a poor, dowdy governess who was sent by an employment agency to an incorrect address where she meets Miss LaFosse, a glamourous night club singer. Indeed, the author of a The Happy Tree by Rosalind Murray was mentioned intriguingly in Virginia Wolf’s Diary; this inspired a search and eventual publication.

It is refreshing that the company does not publish books which are purposely avant-garde, playing games with time, language, punctuation and syntax, what one could find in the library of an ivory tower. Intelligently written in accessible language, they draw us into the pages. They are remarkable for being so remarkably human. And, yes, the non-fiction can be revelatory, too. How we ate and gardened then is a guiding light for how we eat and cultivate our garden now.

Persephone Books should be proud about focussing on the nature of the human terrain, the nurturing of the nest, for this is the very essence of humanity. Will you join the list?

Please visit http://www.persephonebooks.co.uk/for more information.