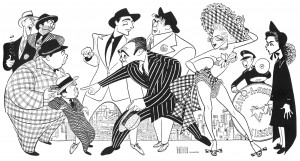

Years ago, when I was a little girl growing up in New York City, one of my favourite Sunday morning pastimes – after the de rigeur brunch of scrambled eggs and bacon of course – was searching for the word ‘NINA’ hidden in the drawing by the legendary American illustrator, Al Hirschfeld, of an opening night scene from a Broadway play on the front page of The New York Times Arts and Leisure section. In each sketch Hirschfeld inscribed his daughter’s name – NINA – in the right hand corner next to a number between one and ten. The number of specified NINAs might be found in the ruffles of a collar, the jewels of a tiara or the creases of a bow tie. In fact, thousands all over the nation played this parlour game. Al called it ‘harmless insanity’.

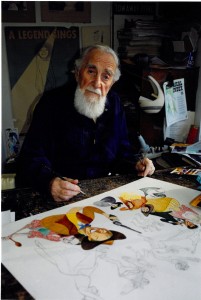

Years ago, when I was a little girl growing up in New York City, one of my favourite Sunday morning pastimes – after the de rigeur brunch of scrambled eggs and bacon of course – was searching for the word ‘NINA’ hidden in the drawing by the legendary American illustrator, Al Hirschfeld, of an opening night scene from a Broadway play on the front page of The New York Times Arts and Leisure section. In each sketch Hirschfeld inscribed his daughter’s name – NINA – in the right hand corner next to a number between one and ten. The number of specified NINAs might be found in the ruffles of a collar, the jewels of a tiara or the creases of a bow tie. In fact, thousands all over the nation played this parlour game. Al called it ‘harmless insanity’.Sometimes I would shriek with joy, not because I had succeeded in my hunt, but because a personality in the picture had visited our apartment. My father was a television producer who by virtue of his profession had become acquainted with many glitzy people in stage, screen and television. You can imagine my astonishment when a couple of decades later a great family friend, Louise Kerz, a theatre historian, became Hirschfeld’s third wife. His second wife of forty-two years, Dolly Haas, a Berlin born actress, had died two years previously.

In fitting with his quirky and unassuming character, Hirschfeld’s route to fame and good fortune was marked more by serendipity, rather than plan. He had the noble gift of being able to take advantage of opportunity without being an opportunist. Although certainly not born with a silver spoon in his mouth, it is likely that Hirschfeld entered the world in 1903 with a pencil in hand. Before he could read he was drawing portraits of his nursery school mates. His father, Isaac, was from Albany, New York. As a travelling salesman, he met his wife, Rebecca, a Ukrainian immigrant, in St. Louis. Somehow the couple managed to fall in love despite the fact that she spoke only Russian and Yiddish and Isaac spoke only English. They settled in St. Louis where Mrs. Hirschfeld ran a sweet shop. When Al’s family moved to New York during his teens, he became fascinated with baseball, playing on a semi professional basis, and the theatre. He studied lithography, learned to tap dance and play the ukulele.

Hirschfeld’s working life began in film rather than theatre, penning illustrations for motion picture studios that were used to encourage distributors to market the productions. What probably sparked Hirschfeld’s focus on caricature was his friendship with the Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias. The young Carvarrubias was a celebrated cartoonist at the time, though compared with Hirschfeld’s work his was less flattering, not shy of the deforming or the ugly, and relatively more dimensional – ‘cubist’ given its obvious geometric shapes. It reflected, too, Covarrubias’s developing interest in ethnographic art. Indeed, later Covarrubias became an anthropologist.

At aged eighteen Hirschfeld became an art director with Selznick Pictures, and when the firm went bankrupt he went to Paris and led the clichéd existence of the young artist contemplating the meaning of life in cafés where Hemingway and Picasso frequented. He also travelled to Spain, Morocco, Russia, Bali and Tahiti. He savoured the discovery of unfamiliar settings to illustrate, especially the Far East where he began to develop what was his particular style, ‘seeing in lines’ and drawing only in black and white. He had a theory that European artists painted in bright colours as a reaction against the foggy, damp, gloomy climate. He wondered if great graphic art originated in the Far East because there the sun was always relatively bright.

‘There’s something about the sun that takes out all the colour and leaves shadows. There’s very little colour left on the beach. It’s all black and white, and you begin to think in terms of line. I think this has a profound influence on the artists of these countries,’ Hirschfeld is quoted in the 2000 publication Hirschfeld On Line. His attraction to line precision is what made him admire such Japanese artists as Hokusai and Harunobu.

Once home in New York, an ‘accident’ spawned the course of Hirschfeld’s career. While at the Broadway play, Deburau, Hirschfeld sketched a caricature on his programme of the French writer and star of the show Sacha Guitry. This was spotted by the show’s publicist who placed the picture in the following Sunday’s Herald Tribune. A star was born: and in time commissions for drawings of people in the performing arts and politics for newspapers, magazines and publicity posters followed as quickly as pages hot off an old fashioned printing press. His subjects became his friends and producers looked to him for advice; many of his admirers attended the lavish parties he and Dolly gave at their home in New York’s fashionable Upper East Side.

Hirschfeld overcame the handicap of having to draw in the theatrical dark by practising with a pencil stub, using a small notepad and sometimes a flashlight. ‘I eventually learned to draw in my pocket. My system is a kind of shorthand I alone can decipher. Written words and hieroglyphic signs help me defeat the darkness. Seated out front on the aisle…I start sketching at the rise of the curtain. Later, back in my studio, I correlate words and pictures into a designed composition for the finished drawing.’

Hirschfeld overcame the handicap of having to draw in the theatrical dark by practising with a pencil stub, using a small notepad and sometimes a flashlight. ‘I eventually learned to draw in my pocket. My system is a kind of shorthand I alone can decipher. Written words and hieroglyphic signs help me defeat the darkness. Seated out front on the aisle…I start sketching at the rise of the curtain. Later, back in my studio, I correlate words and pictures into a designed composition for the finished drawing.’

What is particularly unique about Hirschfeld’s pictures is that they are not malicious; they never ridicule, mock or enter into the realm of the grotesque, as do those of his forbears, Hogarth and Cruikshank. His people are never ugly. Physical reality is exaggerated merely because the exaggeration draws out the spirit of the character. Hirschfeld used landscape to shed light upon a person, but he did not record the nature of the inanimate for their own sake. Commenting his style, Hirschfeld’s archivist, David Leopold, has written:

Where others rely on complicated pictorial detail, his drawings have a self-evident air, as if every line could be in no other place. While eliminating indeed purifying the detail of his pictures, he also enriches and intensifies the viewing experience by communicating volumes in a single stroke.

The actress Ethel Merman’s guts and determination, her strong, clear and forceful voice in and out of character as mother of Gypsy, is accentuated by her large chest, full cheeks and open mouth. Emphasising Elizabeth Taylor’s ‘big eyelashes, big eyebrows, big eye shadow’ – this was the Sixties! – reminds us of her glamour and seductive allure as a woman and actress. Katherine Hepburn’s little dots for eyes and nose capture the sense of physical frailty she exudes as Laura in The Glass Menagerie. Hirschfeld says, ‘she’s been turned into one of the glass figures in the play.’ He does not seek to pass judgement but rather to portray what is interesting or memorable about a person. One could suggest Hirschfeld had a compassion for humanity, thinking of himself as a ‘characterist’. He felt drawn to people and absorbed by them, and what he saw as their essence. His work celebrated folk; it was not a means of coping with frustration, anger or melancholy.

The cartoonist Mel Calman appreciated that ‘there’s a lot of warmth and affection in his drawings too, not the awful bile and hostility you get so often nowadays’. Arthur Miller wrote that

looking at a Hirschfeld drawing of yourself is the best thing for tired blood. The sheer tactical vibrancy of the lines and their magical relationships to each other make you feel that all is not lost, that you still have a way to go before bed, that life can be wonderful, that he has found a wit in your miserable features that may yet lend you a style and a dash you were never aware of in yourself.

Less well known is Hirschfeld’s political work that is to say mostly covers for such magazines as the Marxist Left wing New Masses and the intellectual and satirist American Mercury, edited by H.L. Mencken. One must not overlook too his fascination with the Harlem Renaissance movement – which he shared with Covarrubias. The colour illustrations in his 1941 book Harlem (since expanded and reissued in 2004), a recollection of black writers and jazz performers in speakeasy times, are rich source material for social historians.

Official celebrations of Hirschfeld’s work have included two Tony awards for lifetime achievement and commissions by the United States Postal Service for stamp designs devoted to comedians, silent screen stars and vintage black cinema. Some of the images have hidden NINAs.

Hirschfeld died in 2003, a few months short of his one hundredth birthday, and not long before he was to be honoured as a Living Landmark of New York, one who has made an outstanding contribution to the city. Interestingly, New York’s state schools’ arts curriculum focuses on his work as a means of educating pupils about the visual and performing arts in the twentieth century. For what his work brought to life is now part of printed history. Alas, when one reflects upon the character of Hirschfeld and his achievement, one realises there will never be another quite like him.

Notes:

My thanks to Louise Kerz Hirschfeld and David Leopold, The Al Hirschfeld Foundation Archivist, for their support and choice of illustrations courtesy of The Al Hirschfeld Foundation. For more information, please visit http://www.alhirschfeldfoundation.org

The images above feature Guys and Dolls, 1950 and the great man himself. They are printed with the courtesy of the Al Hirschfeld Foundation, © The Al Hirschfeld Foundation, all rights reserved.

The article first appeared in The Art Book, May 2010, Volume 17, issue 2.