During your Covid permissible walks throughout London, did you ever stop to look at the blue plaques we see on buildings all over the capital? They link places with people notable in history for their achievements. Almost all of the  people commemorated will have lived and or worked in the buildings to which the plaque is attached. Sometimes when I have seen a name on a blue plaque I have made a mental note and when I have returned home, I have tried to find out more about the person honoured. Not all the names are familiar nowadays, understandably. Many of the stories behind the names are fascinating, social histories one could say. Even when you know the name and what the so named person is famous for, you could be surprised by what more you can learn about them.

people commemorated will have lived and or worked in the buildings to which the plaque is attached. Sometimes when I have seen a name on a blue plaque I have made a mental note and when I have returned home, I have tried to find out more about the person honoured. Not all the names are familiar nowadays, understandably. Many of the stories behind the names are fascinating, social histories one could say. Even when you know the name and what the so named person is famous for, you could be surprised by what more you can learn about them.

For example, if you stop outside 13 Mallard Street in Chelsea you will see the plaque dedicated to the author AA Milne (1882 – 1956) who lived at this address. I know that you know that he wrote the splendid stories about Winnie the Pooh and wonderful poems. But, once at home, you could discover that he liked to play cricket and that the cricket team Milne belonged to also included – at various times – J.M. Barrie, H.G. Wells, Jerome K. Jerome, Rudyard Kipling, Arthur Conan Doyle, PG Wodehouse and GK Chesterton. Barrie formed the team.

You could also discover that Milne read books by Jane Austen and that he wrote plays and a successful detective story called The Red House Mystery. Although Milne was a passionate pacifist, he served in World War 1 as a signalling officer and saw action on the Somme because he wanted to serve his country. Indeed, Milne wrote a book called Peace With Honour, published in 1934, which was a plea for pacifism.

“It is because I want everybody to think (as I do) that war is poison, and not (as so many think) an over-strong, extremely unpleasant medicine, that I am writing this book,” he wrote in Peace With Honour. “The last war involved women and children and the accumulated wealth of civilisation in slaughter and ruin. The next war will involve them in a much greater slaughter and ruin. This seems to be a good reason for making the next war impossible.”

However, Milne later wrote War with Honour, published in 1940 which was a marked contrast to his first achievement. “If anybody reads Peace with Honour now,” Milne wrote, “he must read it with that one word HITLER scrawled across every page … I accept the facts, and I accept this war. For German Peace means all that Modern War means — and worse. It means not only the torturing to death of bodies but the poisoning to death of souls … And the ultimate truth which will always be sacred is that the soul is more important than the body.” How many of Milne’s readers know about his feelings about war and how it ravages mankind?

Most do know however that Milne based the animals in the Pooh stories on his son Christopher’s soft toys, Piglet, Eeyore, Kanga, Roo and Tigger. That Eeyore may have been partly modeled on one of Milne’s editors, and that Christopher became a successful bookseller and was not very happy about being so world famous may stray into the world of the unknown.

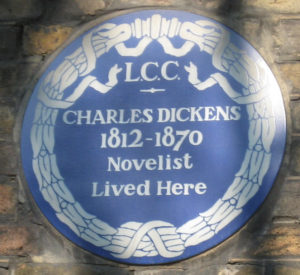

Of course, you could expand you research endeavor and discover that the Blue Plaque scheme was started in 1866. It is run by English Heritage, the charity that cares for 400 historic monuments, buildings and places, such as prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses. In the past the scheme has been run by other organizations. The first plaque was dedicated to the poet Lord Byron, but it was removed when the building was replaced with a department store. There are more plaques in central London than in outlying boroughs such as Wandsworth and Greenwich. There are over 950 blue plaques to see.

To be worthy of a Blue Plaque a person has to be well respected and highly thought of in their field of work or calling and should have made some positive contribution to human welfare and happiness. The individual must have been dead for 20 years or more. English Heritage would like there to be more plaques dedicated to accomplished women.

Blue plaques have not always been blue and round shaped. They have been brown, sage and terracotta and square and rectangular. Some have had a laurel and wreath border. At first they were made by the Minton pottery factory. The next company to make them, Doulton, introduced the blue glaze. Now the plaques are made by Frank and Sue Ashworth and Justin, their son, who live in Cornwall. They use a ‘secret’ recipe with different clays as ingredients to create the plaques. The plaques must be 495 mm (19 ½ inches) in diameter and 50 mm (2 inches) thick. They should note the name of the honoured person, his or her life dates, accomplishment and whether they worked or lived in the building or both.

The MP William Ewart (1798 – 1869) thought of the idea of the scheme. Ewart is commended for his successful efforts to abolish hanging in chains and to abolish hanging for cattle stealing. In his day hanging was considered a proper punishment for criminals guilty of certain crimes such as murder or stealing cattle. Ewart also helped to establish free public libraries.

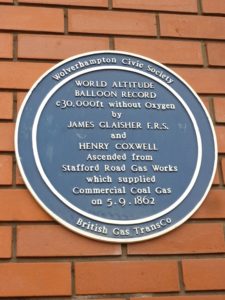

Nowadays, there are many other similar ‘plaque’ schemes throughout the nation dedicated to  individuals and sponsored by charities, local societies and local councils. They may have different qualifying criteria than the Blue Plaque Scheme.

individuals and sponsored by charities, local societies and local councils. They may have different qualifying criteria than the Blue Plaque Scheme.

In the borough of Islington, where I live, there is the Islington Heritage Plaques scheme which commemorates “the significant people, places, and events in the borough”. There are 102 plaques thus far. I note that the African National Congress had its headquarters at 28 Penton Street. Nina Bawden (1925 – 2012), the author and campaigner for railway safety, lived at 22 Noel Road, near the canal. On Hungerford Road, at 141, there was once a Roman camp site.

One could suggest a wealth people, places and historic events to honour. Who and what springs to life in your mind?

***