On the wall in our dining room there is a photograph of Queen Victoria in a carved black wood frame with a purple mount. She is sitting, looking to one side of the camera, with a dog on her lap. The Queen’s stout body is dressed in mourning black, her face wrinkled and jowled, her thin lips tightly pressed together, her eyes watery – a dour woman, drenched in sorrow. I think of the image when I visit the Victoria Art Gallery in Bath, for its outside is rather austere, foreboding, like the sad Queen, despite the building’s Classical proportions and architectural features, such as Ionic columns and friezes with mythological figures. It has a municipal air too, reminiscent of stony town hall edifices, where unyielding officialdom rules.

On the wall in our dining room there is a photograph of Queen Victoria in a carved black wood frame with a purple mount. She is sitting, looking to one side of the camera, with a dog on her lap. The Queen’s stout body is dressed in mourning black, her face wrinkled and jowled, her thin lips tightly pressed together, her eyes watery – a dour woman, drenched in sorrow. I think of the image when I visit the Victoria Art Gallery in Bath, for its outside is rather austere, foreboding, like the sad Queen, despite the building’s Classical proportions and architectural features, such as Ionic columns and friezes with mythological figures. It has a municipal air too, reminiscent of stony town hall edifices, where unyielding officialdom rules.

Ah, but once you step inside, the interior strikes you with a sense of the youthful, vivacious Queen Victoria, deeply in love with her Albert. The atmosphere buzzes and enthuses, and the eclectic exhibits, both permanent and temporary, are consistently interesting. Moreover, the gallery is always filled – but never uncomfortably packed – with people of all ages who look as if they really are enjoying the art. This regional artistic pearl is one of my favourite ‘local’ museums alongside the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge and the Clark Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, both well endowed – unlike the Victoria Gallery – and much larger.

The gallery is a civic memorial to Queen Elizabeth’s great ancestor Queen Victoria. When, in 1896, a local resident bequeathed the sum of nearly £10,000 to help establish Bath’s first public art gallery, the Mayor of Bath easily raised the additional £4,500 needed for its construction. Undoubtedly, potential donors were inspired by the fact that 1897 would be Queen’s Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. Appropriately, the gallery was named after her; and a Portland stone statue of the Queen by Andrea Carlo Lucchesi was placed in a central niche on an exterior wall.

Centrally sited, the gallery stands on a descent sloping toward Pulteney Bridge, partly facing the River Avon. The building was designed by the Scottish architect John McKean Brydon (1840–1901), notable for his additions to the Pump Room (this was a Concert Room) in Bath and London’s Chelsea Town Hall, and designs for the Chelsea Library, the Treasury Chambers in Whitehall and several London hospitals. The first floor features an extremely spacious top-lit gallery, with an attractive coved ceiling, while the ground floor consists of two spaces for temporary exhibitions, one quite vast and remarkably well lit; originally the ground floor spaces formed a library and print room.

Unlike many of the great national museums, the Victoria Art Gallery, is very much both a ‘people’s gallery’ and a local people’s gallery. When first established many ‘natives’ donated their works of art to form its permanent collection; to this day much of the permanent collection is from spirited local people, though increasingly arts-oriented funding helps to purchase acquisitions.

‘My philosophy is that the gallery is first and foremost a local gallery; we exist for the people of Bath and Somerset. We wouldn’t be here were it not for the generosity of local people who donated the treasures on their walls to share them with the public, says Jon Benington, Manager and Curator of the Gallery. Benington recalls the exhibition Saved For Ever, held in 2011, which celebrated the generosity of local benefactors, together with their gifts.

‘I feel so pleased and happy,’ wrote Alice Dorothea Henderson in 1946, ‘knowing that the things I live with will be housed and cared for in such a lively art gallery and beautiful old city’. Her gifts included the most popular picture in the Gallery, Watersplash, by Henry La Thangue. Other highlights include The Adoration of the Magi, attributed to the circle of Hugo van der Goes, Gainsborough’s portrait of Captain William Wade, 1770–1, a bronze bust of William Harbutt, 1911, by Edwin Whitney-Smith (Harbutt invented Plasticine, for many years manufactured near Bath), and a Small Harbour Scene, 1919, by Paul Klee.

‘There’s is no real science to knowing what shows will succeed and which will fall flat,’ believes Benington. But despite his perspective, there must be a touch of wizardry about the man for there have been quite a few exhibitions in the past 15 years, since his arrival, which have been not only innovative but also of great local and wider appeal. The most successful in terms of visitor numbers (34,000) was the Blue and White Show, held in 2008, which embodied a very English tradition: collecting blue and white china, and was inspired by a collection of over two thousand pottery pieces belonging to the Hickman family of Cornwall.

Highlights were displayed on a vast, specially designed Georgian-style dresser. Three major contemporary artists with local connections presented exhibits inspired by ‘blue and white’: Kaffe Fassett (famed for his innovative knitting and needlepoint), Carole Waller (also praised for her unusual textiles) and Candace Bahouth (known for her mosaic-covered shoes and furniture – her mosaics could include fragments of Spode’s Italianate patterns, for example). The guest curator was another local, Deidre McSharry, a former editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan magazine.

The second most successful exhibition, held in 2010, featured the photography of Somerset-based Don McCullin, whose work, spanning a 50-year career, has had a great influence our views about war, awakening us to the horrific reality of modern conflict. We viewed McCullin’s gentle, atmospheric work as well as the shocking examples: his early photographs of working-class North London, still lifes and landscapes, and the shattering revelations of political and ethnic strife. Another innovative exhibition, also held in 2010, was the first-ever show devoted to the Cornish and Provençal landscapes of Matthew Smith (1879–1959), a Royal Academy colourist.

Each year the gallery hosts the Bath Society of Artists Exhibition. The Society, founded in 1904, aims to foster the ‘creative activity of artists, professional and amateur, in Bath and its environs’ and to inspire local interest in art. The Exhibition is open to non-members; works are for sale and prizes awarded. Distinguished painters who have exhibited with the Society include Walter Sickert, John Singer Sargent, Gilbert Spencer (a past president and Stanley Spencer’s brother), Mary Fedden (a past Vice President) and Howard Hodgkin.

Indeed, the gallery has a history of ground-breaking beginning in 1918 when it held an exhibition of Impressionist paintings from the collection of the Davies sisters of Gregynog, Wales. Their collecting advisers were John Witcombe, a curator of the Gallery, and Hugh Blaker, a curator at Bath’s Holburne Museum – strong regional links. Many of the art historian W.C. Constable’s contemporary comments on the show in The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs are still valid today in discussions about the educational and life-enhancing importance of exposing those who live away from major city centres to a wide range of art.

[The] exhibition of modern painters …is an event of some importance; not only because it includes work by such painters as Cézanne, Daumier, Gauguin, Renoir, Manet and Monet, but also because of the example it affords to public galleries throughout Great Britain. Outside of London, the public have little or no opportunity of understanding the true character of modern art…or even of seeing tolerable works by old masters…by means of loan exhibitions such as the one at Bath, it would be easy to show, not only representative works by painters of the past, but typical and important examples of contemporary painting; and thereby to make it known that modern art does not centre entirely in Burlington House [now the Royal Academy]…the best way to interest people [especially in modern art and its application] is to put interesting pictures on view…

And perhaps in homage to this iconic show, the exhibition Sisters Select of works on paper – prints, drawings and watercolours by such artists as Cézanne, Turner and Blake, also from the Davies Collection (housed at the Museum of Wales, Cardiff) – featured at the gallery in 2011. A return visit!

Fortunately the local authority continues to run the gallery in spite of pressures to reduce its overall budget, and although many of the works of art cannot be exhibited owing to lack of space, they can be seen by appointment and through public ‘behind-the-scenes’ tours. Others hang in arts establishments in Bath such as the Assembly Rooms; the permanent displays are rotated frequently and often arranged according to local themes; community groups are invited to curate their own ‘People’s Shows’. The ‘Adopt a Picture Scheme’ enables individuals and businesses to display artwork on their walls for a year if they sponsor its conservation.

Two years ago the Gallery recorded its highest-ever annual attendance figures of 116,000. (The Fitzwilliam records about 300,000 and the Clark about 175–200,000.) The Victoria Art Gallery, given its relative size and limited resources, should be proud that it attracts so many. ‘To see lots of people coming through the doors,’ enthuses Benington, ‘it’s better than money.’ And this would make the sad Queen smile.

For information about the Gallery’s opening hours, exhibitions, educational programmes, family activities and tours, please refer to http://www.victoriagal.org.uk/

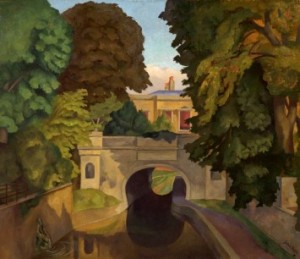

Image of painting by John Nash, Canal Bridge, Sydney Gardens, Bath (c.1927), courtesy of the Victoria Art Gallery.

This article first appear in Cassone: The International Online Arts Magazine of Art and Art Books in the September 2012 issue.