To celebrate our anniversary, we went to Madrid. It was our first visit. We chose Madrid partly because it is the home of Nancy, the sister of a friend from my New York schooldays, and her husband José.

The four of us arranged to meet outside the Prado. I had not seen Nancy for many, many years, but I recognized her immediately. She still had the almost flush, pinkish glow, the wavy, reddish blonde hair and the deep, authoritative voice, spoken from the diaphragm, that she had when we were teenagers. With Nancy in the lead, we strolled to the Circulo de Bellas Artes of Madrid, a private cultural establishment dating from 1880. There one finds a cinema, theatre, lecture and exhibition halls, artists’ workshops, a library, a café and restaurant. Its present home was designed by Antonio Palacio, a Spanish architect notable for his powerful and monumental designs. We ventured to the top of the building to gaze at Madrid’s rooftops.

Having sensed that we felt a little overwhelmed by the Prado – there was so much to see and digest in this vast museum, and it was very crowded – Nancy suggested that we went to the Circulo’s mezzanine to see an exhibition of rediscovered Spanish Civil War negatives by the photojournalists Robert Capa, Gerda Taro, and ‘Chim’ (David Seymour). The material was found in 2007, in a suitcase in Mexico. We savoured the intimacy of the galleries and having the time and space to think about the disturbing images and the circumstances surrounding them.

The next morning, again thanks to Nancy, we discovered the José Lázaro Galdiano Museum, in Madrid’s quiet and elegant Salamanca district. An obituary written for the College Art Journal by Walter Cook, a former director of the New York University Institute of Fine Arts and scholar of Spanish art, said that José Lázaro Galdiano (1862–1947) will be remembered for his ‘passion for great masterpieces of art, his animated and vivacious spirit, his gracious courtesy and charming personality’. Unfortunately, this distinguished patron of the arts is not well known or appreciated outside Spain; and there are few substantial sources in English that explore his life, work and art collection.

Upon his death, Galdiano bequeathed his art collection, library and magnificent Neo-Renaissance residence, Parque Florido Palace, to the Spanish government. Afterwards, in 1948, the Fundación Lázaro Galdiano was established in order to house the library and undertake further research about Spanish culture. (The Foundation’s offices are next door to the Museum.) The collection was housed in Galdiano’s former residence, which was opened to the public in 1951. (Cook, in 1962, described its ‘early days’ in the Art Journal, but the building was extensively refurbished recently to display about half the collection in a relatively more themed and ordered manner.)

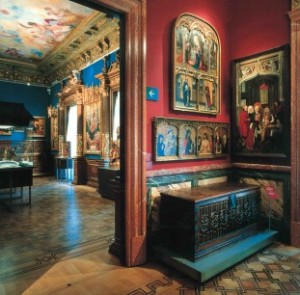

Galdiano’s eclectic art collection, of some 13,000 works, was amassed for the most part while travelling with his wealthy Argentine wife, Paula Florido, and during extended stays in New York and Paris. Our visit revealed an extremely rich collection of treasures chosen for their value as objects of history, rarity or beauty: secular and religious manuscripts and engravings, jewellery, ivories, enamels, bronzes, fans, textiles, medals, armour and furniture, representing various periods and styles, such as Hellenistic, Islamic, Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque.

Spanish works of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries predominate among his paintings. One room, the former entrance hall of the mansion, is devoted to court portraits of grand ladies of the aristocracy. Perhaps the only work by a woman painter in the collection is Portrait of a Young Lady, attributed to Sofonisba Anguissola, a court painter to Philip II and lady-in-waiting to Elisabeth of Valois, the King’s third wife. The well-poised woman, sumptuously adorned – the intricate designs of the fabrics are exquisitely detailed – looks so pure and vulnerable.

Spanish works of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries predominate among his paintings. One room, the former entrance hall of the mansion, is devoted to court portraits of grand ladies of the aristocracy. Perhaps the only work by a woman painter in the collection is Portrait of a Young Lady, attributed to Sofonisba Anguissola, a court painter to Philip II and lady-in-waiting to Elisabeth of Valois, the King’s third wife. The well-poised woman, sumptuously adorned – the intricate designs of the fabrics are exquisitely detailed – looks so pure and vulnerable.

Equally notable are works by Sánchez Coello, Zurbárin, Ribera, El Greco – his Saint Francis of Assisi is outstanding – Murillo and Velázquez. There is a room dedicated to Goya, and I was grateful for the time and space to think about the sinister beauty of The Witches and his Witches Sabbath. In the 19th century, as generally elsewhere in Europe, artists and viewers heralded the common man and social realism, journeying far away from divinity towards the raw spirit of the secular. One fine example is a warm, certainly not grand or pompous, portrait of a friend of Galdiano’s, The Critic Luis Alfonso, by Emilio Sala.

Galdiano was determined that his collection should be a tribute to Spanish art history in particular, a reference for educating his compatriots about Spanish art. In this vein, he is commendable for including Spanish Gothic and Renaissance panel painting, once scorned for being ‘primitive’ art. The examples reveal the different artistic techniques and influences that were once prevalent throughout Spain and could be categorized in a regional context. For example, in the Castilian school one can discern the influence of Flemish realism as the saints look more human and expressive than in the panels associated with the Aragonese School, wherein the faces of the saints are more idealized.

On the second floor, one finds works by Dutch (Hieronymus Bosch’s Saint John in the Desert, for example), German (including works by Cranach the Elder and Younger), Italian (paintings by Magnaso and Cavallino, for instance) and French artists (including a still life by Dussilion the Elder). One also finds paintings by English artists such as Gainsborough, Reynolds, Constable and Lawrence – an unusual occurrence as works by English painters do not abound in Spain. It is believed that Paula Florido particularly warmed to the English painters. The entire Galdiano collection is decidedly historical, not modern.

The first floor former ceremonial rooms used for display are particularly remarkable for their elaborate architectural detail and imaginative ceiling paintings by Eugenio Lucas Villamil. On one ceiling, there are allegorical scenes of the Four Seasons, while another celebrates musical genius, revealing composers such as Richard Wagner, Beethoven, Liszt, Chopin, Rossini and Verdi. Other ceilings celebrate poets and writers, such as the playwright Lope de Vega, and deities from classical mythology. A pleasant garden surrounds the house.

The museum offers visitors an education and the perfect atmosphere in which to reflect upon the cultural and social history of Spain with which many of us might not be familiar. On a warm peaceful Sunday morning it is the ideal discovery. A touch romantic too.

Notes:

Lázaro Galdiano was born in Biere, Navarre. He studied philosophy, literature and law and then he settled in Madrid and became a financier, enterprising publisher and distinguished art collector. For many years he was a member of the board of trustees of the Prado Museum, and a director of the Banco Hispano Americano in Madrid.

Lázaro’s renown in Spain as an art patron started to develop when he heroically tried to prevent the sale to the German government of a painting by Hugo Van der Goes, The Adoration of the Wise Men, which had belonged to the convent of Escolapios at Monforte. The Fathers wanted to sell the painting to pay for extensive building repair.

The possible sale of this picture incited protest throughout the Peninsula. Lázaro opened a subscription to save the picture for the nation, and campaigned through lectures and newspaper articles. (Unfortunately he failed and the picture now hangs in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin.) Galdiano also earned reverence for his generosity when, during the Moroccan War, he donated prizes to the value of 10,000 pesetas for the soldiers who wrote the most patriotic and affectionate letters to their mothers.

Galdiano founded España Moderna, which published the Revista Internacional journal, covering cultural and judicial topics, and the Biblioteca de Jurisprudencia Filosofia e Historia, for which some 600 volumes appeared. But his most fertile endeavour was the establishment in 1889 of the Spanish cultural and historical review La España Moderna – Revista Ibero-Americana. The foremost writers and critics of the time were contributors. The journal closed in 1914. Professor Robert Hilton, a scholar of Spanish culture, commented that Lazaro ‘was clearly an organizer and promoter rather than a writer. We have relatively few products of his own pen’.

For further information regarding the Museum Lázaro Galliano, please refer to www.flg.es/fundacion/fundacion.htm.

Images featuring the exterior of the Museum and Rooms 7 and 8 with 15th and 16th century Spanish art, courtesy José Lázaro Galliano Museum.

This article first appeared in Cassone: The International Online Magazine of Art and Art Books in the December 2012 issue.