Recently, my friend Barbara gave me a yucca plant. ‘It’s from Adrian,’ she said. Adrian, her partner, had been like a father to me when I was in my late teens, inspiring my studies in anthropology. I’d met him when I was a gap year intern with a British television company. Adrian made award-winning films about the ravages of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. He died a few weeks ago, aged 77.

Recently, my friend Barbara gave me a yucca plant. ‘It’s from Adrian,’ she said. Adrian, her partner, had been like a father to me when I was in my late teens, inspiring my studies in anthropology. I’d met him when I was a gap year intern with a British television company. Adrian made award-winning films about the ravages of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. He died a few weeks ago, aged 77.

The yucca, Adrian’s living memorial, came from a London nursery, although its origins are rooted in faraway regions, such as Brazil. But were it not for greenhouses (including the miniature ones called Wardian cases, which were kept on board ships), providing shelter for explorers’ green discoveries, we wouldn’t enjoy its presence today, and indeed a healthy proportion of the fruit and vegetables we eat – chilli and tomato risotto, for instance.

We put the yucca in our conservatory, an extension of the kitchen. It makes me feel as if I’m in our verdant garden, yet protected from the chill, damp and drizzle of the British climate. It’s simply a pleasant living space, a contemporary alternative to creating larger rooms with brick walls and sash windows, rather than a place for cultivating plants. But this certainly was not the case a couple of thousand years ago with the embryonic conservatory.

When sketching conservatory evolution, it’s worth noting that throughout history various terms have been used interchangeably for what may be the same sort of construction for the same sort of purpose: glass house, greenhouse, conservatory, stove house, roomstead, winter garden, sun room, loggia, orangery. My super weight Oxford dictionary says the original (16th-century) meaning of the word, now obsolete, was ‘a thing which conserves’.

Nowadays, the conservatory is for relaxation, botanical education, enterprise (shops, studios, restaurants) and swimming pools, while the greenhouse is for cultivation and shelter – herein aesthetics play second fiddle. But when it comes to the tangle of historic nomenclature, it’s probably easier to use the owners’ names.

The seeds of conservatory history lay with little houses enclosed with mica slabs, evidence of which archaeologists have found in Pompeii. Mica is a rock that is transparent when split into sheets. Inside, stoves or beds heated with manure could have been for forcing growth, such as that of cucumbers for Tiberius Caesar. In botanical and herbal gardens of the Renaissance there were ‘watersheds’ and ‘plant chambers’ and ‘greenhouses’ such as the one used by the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries in London (the Chelsea Physic Garden).

In Italy especially, but also elsewhere, orange and lemon trees, myrtles, oleanders and pomegranates, imported from warmer climes, were prized and cultivated. During the colder months, temporary wooden houses were built around them for protection. In some instances the plants were moved to a dry cave for preservation, or to stone, brick-clad buildings. The buildings – often termed orangeries after the fruits inspiring their creation – were likely to have had wide floor-length windows (not necessarily glazed), spaced between columns or pilasters supporting entablature, and solid lead or slate roofs, giving a classical appearance. Some buildings were heated with wood-, peat- or coal-fired stoves, and, in time, with steam or hot water conducted through underground pipes covered with wrought iron grilles.

From the late Renaissance onwards, in Britain and on the Continent, gardens evolved into stunning endeavours, displays of aristocratic prestige, wealth, power; garden buildings became integral parts of the overall design, architectural toys. In 1609, King James and his wife, Anne of Denmark, included an orange house and banqueting house in their renovation plans for Somerset House in London. Louis XIV, the ‘Sun King’, commissioned the design and building of a vast glazed stone orangery for Versailles. There were also greenhouses of no aesthetic merit on estates, for cultivation rather than display, and hence hidden from view.

Eventually, as more ‘orangeries’ were built, their shapes and uses became more adventurous. They could resemble classical temples, gothic castles, and Palladian villas, or evoke a sense of the oriental or Indian. One house, built for the Earl of Dunmore in Scotland, was shaped like a pineapple. (It’s now let as a holiday cottage by the Landmark Trust.) Inside these structures could be pools with fish and alligators and lily pads, grottoes, statuary, fountains and birds as well as wondrous exotic plants – and sumptuous entertainment.

The conservatory came later to the United States than to Britain and Europe. After the Civil War, colonial gentlemen, particularly those living on the Eastern coast, looked to Britain for inspiration and began to build vast ornate conservatories on their estates. For the great industrialists, the ‘new’ aristocracy of the New World, they were a means of confirming their social prestige. G.W. Vanderbilt commissioned one such extravaganza for his estate (now open to the public), Biltmore, in North Carolina. Unusually it has a semi-basement, which houses offices and storage, and opens on to vistas of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

The 19th century heralded automated heating, ventilation and watering systems for the conservatory. John Hix’s descriptions of some initiatives in The Glasshouse evoke thoughts of Heath Robinson’s cartoonist contraptions! Technological developments in metal enabled vast iron and glass constructions: glittering domed horticultural cathedrals. Tall cast-iron supports could sustain high ceilings and provide ribbing. Wrought iron, being malleable, could be moulded into complex decorative patterns, some quite rococo-like. Larger and more durable panes of glass were fabricated. In Britain glass became less expensive after the repeal of the glass tax in 1845. Another innovation was ridge and furrow glazing (long bands of ‘peaked’ or curvilinear glass) for the ‘skin’, to catch the sun’s rays more effectively.

In the private realm a notable example was The Great Conservatory – or the ‘Great Stove’, at Chatsworth, completed in 1841, and credited to Joseph Paxton. It’s reported that in 1843, Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and the Duke of Wellington drove in an open carriage at night down its central aisle, which was lit by 12,000 lamps. When beyond repair, it took six attempts to blow up the ‘Great Stove’.

Two iconic public structures were the Palm House at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, completed in 1848, and Paxton’s Crystal Palace, which featured at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in Hyde Park. The competition-winning design was covered with nearly a million square feet of glass; its vaulted 108-foot span was as tall as Notre Dame Cathedral, and it enclosed 18 acres. To meet the six-month construction deadline, most of the structure was pre-fabricated and assembled on site, a procedure that became increasingly the norm for conservatory construction.

Other public-spirited ventures included the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory in New York’s Botanical Gardens, finished in 1902. The gardens came into being as a result of the vision of Nathaniel Lord Britton, Professor of Botany at Columbia University, and benefactors such as Andrew Carnegie. Another striking example is the Jardin d’Hiver in Paris, completed in 1848, which enclosed a ballroom, café, reading room, patisseries, lawns, fountains and aviaries. Sanatoriums and asylums commissioned conservatories, in appreciation of the therapeutic value of sunlight, plants and flowers. The innovative construction also inspired the design of railway stations such as London’s Paddington and Liverpool Street, and Antwerp’s Centraal, because of the span and the admission of daylight that glass allowed.

Another trend, emerging in the 19th century, was for more modest conservatories, for the middle classes. In this light, the great egalitarian William Cobbett commented: ‘how much better for daughters, or even sons, to assist or attend their mother, in a greenhouse, than to be seated with her at cards…How much more innocent…’. I’m not quite sure how Cobbett would have viewed the belief that conservatories nurtured amorous whispers behind the potted palms!

By the early the 20th century the thirst for both grand and even less assuming greenhouses declined owing to staff shortages, social change and maintenance costs (the First World War took its toll). The extravagance characterizing the imposing private conservatories was no longer held in awe. Many such glass edifices fell into disrepair and were torn down. Conservatories were more likely to be used just for plants, being lean-to additions at the back of a house.

Then, later in the century, a concern for understanding and preserving our environment sparked a renewed appreciation of conservatories’ public instructive value. Botanical gardens become homes for quite original buildings. One such example is the prize-winning Climatron in the Missouri Botanical Garden, opened in 1959. It marked the first time a geodesic dome was used for a botanical structure with climate control. Its transparent skin was suspended from an exterior, skeletal, aluminium-tubed framework. Another use of a geodesic dome is at Cornwall’s Eden Project, which opened in May 2000.

The conservatory makers, Marston and Langinger, find that most commissions are from people with an active interest in gardening and nature preservation, who appreciate the firm’s use of environmentally sensitive materials (e.g. double-glazing, hardwood from protected forests, non-toxic paint, silicone plastic). Peter Marston remembers that when he first started the company in the early 1970s, ‘the idea of the conservatory had so far retreated from public consciousness that I kept having to explain that we did not build music schools!’

It could seem a touch melodramatic to link the ravages of deforestation with conservatories, via the roots of the yucca. But if we don’t take care of all things green there might not be such wonders for these handsome buildings to shed light upon. From little yuccas do big thoughts grow.

Notes:

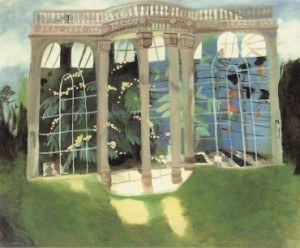

The image is of a painting by Mary Newcomb, Mimosa in the Orangery, 1983. Private collection, Greece. Courtesy of Crane Kalman Gallery, http://cranekalman.com/.

This article first appeared in Cassone: The International Online Arts Magazine of Art and Art Books in the April 2012 issue.