My husband’s ancestors on his father’s side were Greek. In his younger days, he visited parts of mainland Greece in order to discover more about his family history. These past few years he has been studying modern Greek. To put his language skills to the test and share his menu of memorable sites we recently visited the Argolid, a province of the Peloponnese, the southern Greek mainland.

My husband’s ancestors on his father’s side were Greek. In his younger days, he visited parts of mainland Greece in order to discover more about his family history. These past few years he has been studying modern Greek. To put his language skills to the test and share his menu of memorable sites we recently visited the Argolid, a province of the Peloponnese, the southern Greek mainland.

In this region especially, one easily appreciates that Greece is a cradle of artistic heritage. Prehistoric rulers, together with those of ancient Greek and Roman periods, Christian, especially Byzantine, leaders, and Venetian and Ottoman invaders have all left their signature on the aesthetics of the land. There are many contrasting sites to see, not far by road from each other.

The Mycenaean remains at Tiryns and at Mycenae – the sites of the two greatest cities of the Mycenaean civilization – gave the Greek people of Classical times some concrete sense of their own history, apart from what the myths intimated. The Cyclopean walls of the ruins are quite staggering because of their massive, irregularly shaped, boulder-like components, some as wide as 14 metres. Interstices would have been filled with clay and small stones. People of later periods believed they had been built by the mythical Cyclops, members of a primordial race of giants, with eyes in the middle of their foreheads, referred to by both Homer and Virgil.

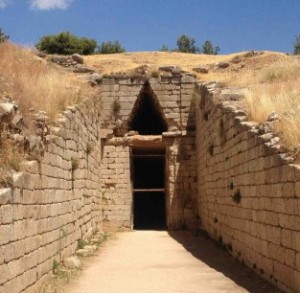

Mycenae was first occupied during the Neolithic (‘New Stone Age’) period, about 4000 BC. The ruins we explore probably originated between the 17th and 13th centuries BC. We step among the fallen stone foundations of the Treasury of Atreus, a well preserved example of a tholos (beehive-shaped) tomb, housing complexes, grave circles, the tombs of the mythological Clytemnestra and Aegisthus, a ‘lion gate’ named for the lions carved above the lintel, and a palace.

Mycenae was first occupied during the Neolithic (‘New Stone Age’) period, about 4000 BC. The ruins we explore probably originated between the 17th and 13th centuries BC. We step among the fallen stone foundations of the Treasury of Atreus, a well preserved example of a tholos (beehive-shaped) tomb, housing complexes, grave circles, the tombs of the mythological Clytemnestra and Aegisthus, a ‘lion gate’ named for the lions carved above the lintel, and a palace.

The focus of public life would have been the palace’s megaron, a rectangular building with a propylon (monumental gateway), a vestibule and a main hall or throne room with a centralized hearth, which is surrounded by four columns supporting a roof with an opening for smoke to escape. This structure, with its relatively crude rock components, is the precursor of the Classical Greek temples. One can venture down an extremely steep, eerie and unlit stairway (try a mobile torch App) with 99 steps, leading to a cistern connected to a spring. Only the ruling class lived on the hilltop. Merchants and artisans lived just outside the city walls. The site was abandoned by 1100 BC. ‘Worked’ gold objects, such as funerary goods, have been found at Mycenae, as well as anthropomorphic and serpentine figures and wall paintings.

Tiryns was first inhabited in the Bronze Age. It was believed to be the birthplace of the heroic Heracles (Hercules), son of Zeus. The ruins we walk through date from the 1300–1200 BC. There is evidence of a palace, tunnels, tholos tombs, and a lion gate. Frescoes and highly decorated floors have been discovered there.

At Epidaurus, a primary centre of healing in the ancient world, we find evidence of what is regarded as Classical Greek architecture and learn that the worshipping of gods of healing dates back to the Bronze Age. During the Mycenaean period, the hero-doctor Malos, or Maleatas, was worshipped at Epidaurus. About 1000 BC Apollo displaced the deity and assumed his name. His cult developed into that of Asklepios, son of Apollo and Koronis, and culminated in the 6th century BC with the foundation of his major sanctuary of healing.

The prestige and reputation of Asklepios as a god of healing attracted many followers to the centre, and generous offerings. This enabled a large building project to be undertaken during the 4th and 3rd centuries BC so that his cult could be housed in monumental buildings. The architect Theodotus designed the peripteral (i.e. having a single row of columns on all sides) Doric temple of Asklepios. Timotheus carved its superb pedimental sculptures. The building material was porous stone; white plaster covered its surface. The flooring was paved with black and white flagstones. Tiles were terracotta. A tholus, mostly constructed of marble, was built next to the temple. It may have housed sacred snakes. The temple’s interior columns have Corinthian capitals; its sculptures are attributed to Polykleitos the Younger, supposedly the architect of the theatre of Epidaurus.

To the north of the temple is the Enkoimitirion, a porticoed edifice in which the sick were required to sleep, so that healing gods could appear to them in their dreams. Priests would interpret each dream in order to determine the prescriptive treatment required. Discoveries of medical instruments indicate that surgical operations were carried out in the sanctuary. There is also evidence of other temples, baths, a gymnasium complex with a stadium, athletes’ and patients’ quarters and an odeion (a small roofed theatre) for musical festivals.

The Roman general Sulla plundered the site’s treasures in the 1st century BC; a little later, pirates ravaged it. New buildings were erected and old ones repaired in the 2nd century AD. In the 4th century AD the Goths ravaged the site. When in 426 AD the Emperor Theodosius II banned the ancient cults, the sanctuary ceased to function. Two major earthquakes in the 6th century AD assured its silence.

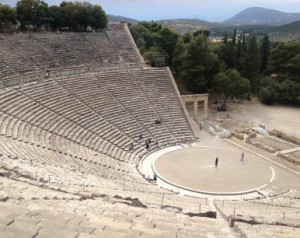

The theatre is most extraordinary, because of its design and perceived relationship to healing. One fully appreciates its vastness, almost perfect symmetry and fine acoustics by climbing to the top, 55th tier. There you hear clearly the voices of people standing on the stage, and survey the verdant landscape. The lower 34 rows are original, dating to the 4th century BC, while the top 21 rows were added in the Roman period (when the theatre could seat 13,000 people as it easily does now.)

The theatre’s circular stage – the orchestra – is 20 metres in diameter. It has a floor of beaten earth. Actors would access the stage through side corridors – paradoi – with monumental gateways. Their pillars have now been re-erected. Remains of the main reception hall – the skene – and what was used as an ‘extension’ of the stage – a proskenion – face the stage. Stairways and walkways enabled access to the theatre’s wedge-shaped sections. The theatre is now host to a summer festival of ancient drama.

Theatres were associated with sanctuaries in the ancient world because the ancient Greeks and Romans believed that drama could be part of the mental and physical healing process; there’s a symbiotic relationship between theatrical performance and convalescence, as there is proven to be with the visual arts. Moreover, in ancient times, many believed in the value of what Plato advocated: ‘an honest and caring relationship’ between doctor and patient. If people think of their healers in a compassionate context, they are more likely to respond to their remedies.

In the Creative Arts Therapies Manual, published in 2006, Sally Bailey, an American drama therapist and social worker, points out that in Poetics, Aristotle says that the function of tragedy is to induce catharsis, cleansing the spectators of pity and fear. Audience members share a commonality of empathy for the characters, making them feel ‘at one’ with the community. Drama, believed the philosopher, helps to release harmful emotions and hence paves the way for a harmonious sense of well being within the locality. Solanus, a 2nd-century Roman, believed that mentally ill patents could be cured by placing them in tranquil surroundings and encouraging them to read, discuss and produce plays. This would help them clarify their thinking and ease their depression. Theatre can be transforming; it literally takes one away from oneself.

For a different perspective of the ancient world, and biblical reference, we visited the ancient city of Corinth, a city-state located on the isthmus joining the Peloponnese to the northern mainland. Corinth is referred to in the New Testament, especially in St Paul’s epistles. St Paul was appalled by what he perceived as the licentious lifestyle of the Corinthian people.

The prosperity of Corinth arose mostly because transporting goods across the isthmus was the shortest route from the eastern Mediterranean to the Adriatic. It made sense for traders to stop and conduct business in the city. Corinthians are credited with the design of the trireme ship and the elaborate Corinthian order of columns seen on some Greek temples.

First inhabited in Neolithic times, in 146 BC the city was pillaged by the Romans, who rebuilt it a century later to include an agora, fountains, the temples of Apollo and Octavia (the three Corinthian columns remaining are especially impressive for their elaborate carvings), a theatre andodeion and a marble-paved road linking the port of Lechaion with the city.

When you explore the Argolid, you will feel as if you have gorged upon hundreds of seeds of a vast cultural heritage. The significance of the sites is overwhelming. You’ll need time to reflect and digest, even if you are an archaeologist.

Notes:

We stayed in the charming and elegant town of Nafplion, visually notable for its Venetian roots. From 1829–34 the town was the first capital of liberated Greece. The narrow, cobbled streets, lined with stuccoed, pastel coloured houses with shuttered windows and clay tiled roofs, the Byzantine style churches, some of which were once mosques, and several of the landscaped symmetrical plazas remind one of Venice or Florence. Over 1000 steps lead to the Palamidi, a large and imposing Venetian citadel affording stunning views over the land and cityscape. (There is a road!) A paved and bougainvillea-lined path borders the coastline. The award winning folk museum with displays of regional costumes and exhibits of rural crafts and local history is housed in an attractive mansion. A Venetian warehouse houses an archaeological museum.

We stayed in the charming and elegant town of Nafplion, visually notable for its Venetian roots. From 1829–34 the town was the first capital of liberated Greece. The narrow, cobbled streets, lined with stuccoed, pastel coloured houses with shuttered windows and clay tiled roofs, the Byzantine style churches, some of which were once mosques, and several of the landscaped symmetrical plazas remind one of Venice or Florence. Over 1000 steps lead to the Palamidi, a large and imposing Venetian citadel affording stunning views over the land and cityscape. (There is a road!) A paved and bougainvillea-lined path borders the coastline. The award winning folk museum with displays of regional costumes and exhibits of rural crafts and local history is housed in an attractive mansion. A Venetian warehouse houses an archaeological museum.

The film, Before Midnight, starring Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke, reveals some glorious settings in the Peloponnese. The story is set at the beautiful home of the late Patrick Leigh Fermor, who settled in Greece. The house reminds one of an old French farmhouse.

For information about visiting times, associated museum collections and facilities, refer to www.culture.gr/culture/eindex.jsp. Many archaeological sites close at 3p.m. despite the many tourists ‘standing at the gates’. The ailing Greek economy could profit from their enthusiasm! Read Robin Leigh Fermor’s Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese.

Photographs of the Theatre at Epidaurus, the entrance to the beehive tomb of Clytemnestra at Mycenae, and Nafplion by Stephen Kingsley.

This article first appeared in Cassone: The International Online Magazine of Art and Art Books in the August 2013 issue.