You will be surprised when you step inside the severe looking neo-classical building, designed by Septimus Warwick, where the Wellcome Collection, in London, lives. There is no sense of the weight of solemnity one might presume lies behind the traditional façade of a world-famous museum and library devoted to understanding and improving health.

You will be surprised when you step inside the severe looking neo-classical building, designed by Septimus Warwick, where the Wellcome Collection, in London, lives. There is no sense of the weight of solemnity one might presume lies behind the traditional façade of a world-famous museum and library devoted to understanding and improving health.

The entrance hall is bright: an airy, open planned space, featuring a reception area, bookshop and café, over which flask-like sculptures are suspended, suggesting the pharmaceutical roots of the Collection’s creation. Many visitors are mesmerised by the Antony Gormley life-sized figure, Feel, hanging upside down from the ceiling, and are captivated by the wall mural, Bernal’s Picasso, depicting the laurel wreathed heads of a winged man and woman. (Picasso sketched the image on a wall in the flat – now since demolished – of the scientist Professor John Desmond Bernal, a friend and fellow peace activist.)

Upstairs are two ‘permanent’ exhibitions. In Medicine Now displays are changed periodically, in order to explore fresh perspectives on global health conditions. One display explores MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) anatomical scans, and electron microscopy, which allows tiny objects to be seen in extremely fine detail. A mostly clear glass sculpture by Luc Jerram of the H1N1 swine flu virus is featured; its delicacy and purity inspire understanding rather than alarm, and its three dimensional, rather than flat surfaces and neutrality of tone encourage peaceful reflection – does intensive farming increase the incidence of swine flu and pose health risks is one of the questions raised by the exhibit.

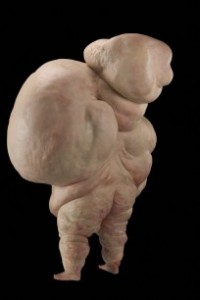

Another theme, ‘Genomes’, the study of genetic sequences of organisms, encourages pondering the social, cultural and political significance of the field. Genomes help trace the evolution of species: who’s related, who’s not. It could enable individual health plans for life. Would knowing about our individual genetic make up influence with whom we share our lives; does this increase the scope for creating ‘master races’? The featureless, purple artwork on display, Jelly Baby 3, by Mauro Perruchetti, is a metaphor for human cloning. The exhibition also considers obesity and malaria.

Another theme, ‘Genomes’, the study of genetic sequences of organisms, encourages pondering the social, cultural and political significance of the field. Genomes help trace the evolution of species: who’s related, who’s not. It could enable individual health plans for life. Would knowing about our individual genetic make up influence with whom we share our lives; does this increase the scope for creating ‘master races’? The featureless, purple artwork on display, Jelly Baby 3, by Mauro Perruchetti, is a metaphor for human cloning. The exhibition also considers obesity and malaria.

Medicine Man, the other permanent exhibition, looks as first like a ballroom-sized cabinet of curiosities, but if you understand the ethos underlying the collection you realise why the objects are featured. Understanding begins with looking at the life of the founder of the Wellcome Collection, Henry Solomon Wellcome (1836–1936).

Probably what drew Wellcome to succeed and share the fruits of his labour was the poverty and struggle that marked his early life on the family farm in the American Midwest. Solomon and Mary, his parents, were very religious; his father was a minister in the Second Adventist Church. When Wellcome was eight, the family moved to Garden City, Minnesota. Solomon wanted some sense of prosperity, lighter work – his health was failing – and to practise his ministry. There the young Wellcome’s entrepreneurial initiative appeared when, at the age of 16, he launched his first product, invisible ink. Following in his uncle’s footsteps, he studied pharmacy and began working with pharmaceutical firms. He travelled to Ecuador, later publishing his research on Cinchona trees – the bark is a source of quinine – to wide acclaim in the pharmaceutical world.

In 1880, Wellcome and a former fellow student, Silas Mainville Burroughs, established a pharmaceutical firm in London. The company became extremely successful by manufacturing and marketing internationally the newly invented compressed medicinal tablets. Their constituents could be accurately measured and tablets were easy to consume, unlike solutions made with a pestle and mortar, and pill slabs. Wellcome coined the trade name ‘Tabloid’ (tablet plus ovoid).

Wellcome had a tremendous flair for publicity, extensively advertising, exhibiting himself and his wares at trade exhibitions, and getting involved with scientific conferences. Unlike many of his colleagues, Wellcome recognised that research is a natural complement to pharmaceutical manufacture. Making and promoting what you sell could be profitable and fund innovative and far-reaching research into eradicating disease. He opened research laboratories in Britain and the Sudan (to target the scourge of malaria) that became renowned for their contributions to health care, such as treatments of diphtheria, tetanus, malaria and leprosy, standardising insulin dosages and enabling the production of antihistamines. He hired outstanding researchers, including Henry Dale, who became a Nobel Prize Winner.

When Burroughs died suddenly in 1895, Wellcome became the sole owner of the business, and this suited a man who was devoted to his work, seldom relaxed, and was not a natural delegator. Although considered courteous, genial, and always willing to listen, Wellcome was unyielding once he’d made up his mind.

Indeed, the fact that Wellcome might not make the most accommodating partner could have been the cause of the unhappiest chapter in his life: his marriage to Syrie Barnardo, the daughter of the philanthropist Thomas Barnardo, in 1901 which ended bitterly in divorce in 1916. Their son, Mounteney, was their only child.

Welcome felt free to develop his collecting interests when he assumed control of the firm, using a global network of agents and contacts to buy from markets, shops, private collections, and auction houses. He wanted to amass a collection of objects, to share with the public, revealing in their entirety ‘the actuality of every notable step in [mankind’s] evolution and progress from the first germ of life to the fully developed man of today’. He was not so much interested in the amusement or aesthetic value of an object, but rather its educative use. For Wellcome, understanding human evolution involves the study of ‘the continuous perils and ravages of disease encountered in the barrel of life’, and how through medicine we have survived.

Medicine Man displays an ethnographic collection because the material culture of indigenous, small-scale societies helps us understand our origins. Anthropological material possesses ‘strong medical significance,’ believed Wellcome, ‘for in all the ages the preservation of life and health has been uppermost in the minds of human beings’.

Hence, when you wander through Medicine Man you will see such artefacts as a 19th-century Bazombo (Angolan) carving of a woman giving birth; friezes detailing the laying of the dead and embalming, and canopic jars used to hold the viscera of mummified bodies, all from ancient Egypt; and a Chinese doctor’s signboard hung with teeth.

Although not strictly speaking ‘ethnographic’, we learn about the human condition from our own history too: there’s a pair of shackles and a pair of handcuffs from Bethlehem Hospital used in the 18th century for chaining up a violent lunatic and furniture and fittings for hospital wards, consulting rooms and pharmacies.

On the floor above, also open to the public, is the Wellcome Collection’s Library. There one can have access to 2.5 million items relating to health: books, paintings, prints, photographs and moving images, archives and manuscripts.

The size of Henry Wellcome’s collection – he amassed over 1.5 million objects – meant that during his lifetime only about one tenth of it was exhibited. The Wellcome Historical Medical Museum he established in 1913 in Wigmore Street wasn’t large enough. Wellcome envisaged premises that would ease the pressure for space and accommodate his research laboratories and offices, but his wish never materialised in his lifetime.

For many years objects lived in packing cases, and eventually it was decided that more people would benefit if parts of the collection were dispersed – on permanent loan – to other museums throughout the world. The famous Wellcome Trust was established after Wellcome’s death thanks to his endowment and is now one of the largest global medical research charities.

Wellcome would be proud to learn that the Collection is embarking upon a development project to increase space for galleries, events, and the library. The current premises opened in 2007 and the Trust has been encouraged by the fact that it recently welcomed its two-millionth visitor. The Collection and all that it so generously encourages ‘runneth over’ with life.

Notes:

Visit www.welcomecollection.org for information about opening hours and events.

Photographs of DNA Spiral, as an interpretation of DNA as an illuminated barber’s pole, made from neon and scientific glass, ©Robin Blackledge/Wellcome Images; and I Can’t Help the Way I feel, 2003, made with wax, polystyrene, steel, expanding foam and oil paint, ©John Isaacs/Rama Knight/Wellcome Images.

This article first appeared in Cassone: The International Online Magazine of Art and Art Books in the December 2013 issue.